Just this week (as I wrote The Sovereign’s Labyrinth), Gael and Keir decided on a late-night excursion through the Glorious Citadel and found themselves scrounging around its library. Which meant that I needed to know how my Hantidans make books.

I tend to borrow very freely from real world history as I build my North-lands, and I already knew that I wanted to borrow from ancient China for my Hantidans’ books. But I didn’t know a lot about bookbinding in the ancient east, so I had to read up.

I tend to borrow very freely from real world history as I build my North-lands, and I already knew that I wanted to borrow from ancient China for my Hantidans’ books. But I didn’t know a lot about bookbinding in the ancient east, so I had to read up.

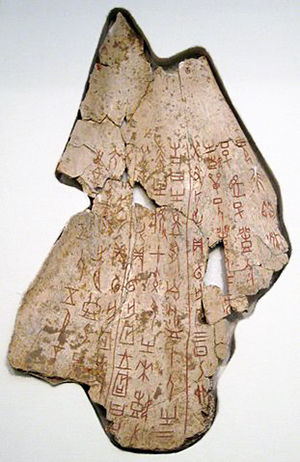

I learned that the earliest writings in significant numbers were found on oracle bones used in divination.

The diviner would submit a question to a deity by carving the inquiry into an ox scapula or a turtle plastron. Then intense heat would be applied via a metal rod, until the bone (or plastron) cracked. The pattern of cracks would be interpreted by the diviner, and his interpretation would be engraved beside the carved question.

A millennium later, the Chinese were writing on bamboo slips which were tied together with silken cords or leather thongs when the text was long and required more space than a single slip could provide. These early books were essentially bundles.

A millennium later, the Chinese were writing on bamboo slips which were tied together with silken cords or leather thongs when the text was long and required more space than a single slip could provide. These early books were essentially bundles.

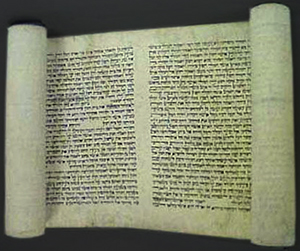

The next innovation was the use of silk made into near-paper for writing. The silk was formed into scrolls, and the writing implement changed from a bamboo stylus to a hair brush.

The transition from bamboo bundles to silk scrolls was not instantaneous, and for a long time both formats remained in use.

Because silk paper was expensive, when a paper made from tree bark, hemp, rags, and fishing nets was invented, it became very popular. It, too, was formatted into scrolls.

Because silk paper was expensive, when a paper made from tree bark, hemp, rags, and fishing nets was invented, it became very popular. It, too, was formatted into scrolls.

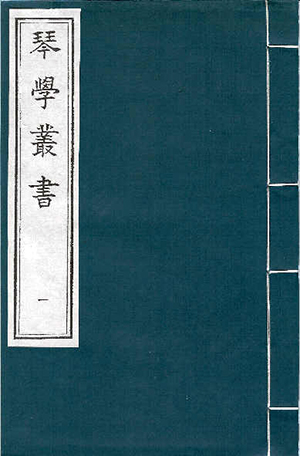

The transition from scrolls to codices began when the long paper of a scroll was folded in wide accordion pleats. Eventually these pleats were cut into separate pages and bound together in a style called butterfly binding. Again, the two forms (scrolls and codices) coexisted for quite some time.

I decided that my Hantidans were in the midst of their own transition from scroll to codex. Scrolls are by far more numerous, but the new codex form is catching on fast!

I decided that my Hantidans were in the midst of their own transition from scroll to codex. Scrolls are by far more numerous, but the new codex form is catching on fast!

But what was the nature of their inks and brushes? Not the traditional quill and ink pot that comes to mind from medieval Europe!

The brushes are ornate and possess caps to protect the bristles during storage.

The inks are made from soot—lacquer soot, pine soot, or oil soot—mixed with glue and aromatic spices, then pressed into shape and allowed to dry to become an inkstck.

When the scribe wishes to write, he grinds the inkstick against an inkstone, pouring water over the ground ink and mixing the two together in the reservoir of the inkstone. The scribe dips his brush into the liquid and then draws on his paper.

When the scribe wishes to write, he grinds the inkstick against an inkstone, pouring water over the ground ink and mixing the two together in the reservoir of the inkstone. The scribe dips his brush into the liquid and then draws on his paper.

Other tools involved in the process of writing are brush holders, brush hangers, paper weights, a rinsing pot, a seal, and seal paste.

This was far more than I needed to know for Gael’s and Keir’s secret visit to the library, but I found it fascinating. Gael and Keir do pass by a desk set with writing implements, but the main action of the scene occurs when another pair of surreptitious night visitors also come to the library!

I won’t say more, lest I stray into spoiler territory. 😉

For more about The Sovereign’s Labyrinth, see:

For more about The Sovereign’s Labyrinth, see:

A Townhouse in Hantida

Quarters in the Glorious Citadel

That Sudden Leap