Modern western culture recognizes 88 constellations. I don’t have that list memorized.

But when I reached a particular point in writing Devouring Light, I grew certain that among those 88 patterns must be a great ape. How could there not be?

I could see Mercurio (my protagonist) conversing with a wise and ancient primate while perched on the massive bough of a rainforest tree in a starry jungle of the eighth sphere. I could hear them speaking.

And there’re tons of animals included in the constellations. The familiar ram, bull, and great bear (Aries, Taurus, and Ursa Major). Plus a boatload of more obscure ones, such as the hunting dogs, the goldfish, and the peacock.

There must be an ape. Or, better yet, apes in the plural.

So I went looking. Eagle, swan, and wolf. No ape.

Centaur, pegasus, and unicorn. No ape.

Even microscope, table, and furnace! But no ape.

What about other cultures?

Traditional Chinese star groupings have the three enclosures – Purple Forbidden, Supreme Palace, and Heavenly Market – and the 28 mansions within them. Among those, the winnowing basket, the turtle beak, the ghost, and the chariot sound pretty cool. But no ape!

Dash it! I’d been sure I’d find a reference to a wise great ape somewhere in oriental star lore. But I hadn’t. And I knew Mercurio met with the chieftain of “elder cousins” manifesting the form of apes.

Luckily…I’m a fiction writer! If I couldn’t find an existing mythology involving apes, I’d create one!

I felt drawn toward language for inspiration, so that’s where I looked next.

The Latin for monkey is simius (male), simia (female), and simiae (plural). My constellation would be the Simiae – the Apes.

What about the English word? What are the origins for the word monkey?

Obscure! It might derive from a character named Moneke in a German version of a fable entitled Reynard and the Fox, published around 1580. Hmm. No juice there. At least, not for me.

I eventually wound up on a Wikipedia page about the Chinese pictograph for monkey.

I eventually wound up on a Wikipedia page about the Chinese pictograph for monkey.

I went looking for that page as I wrote this blog post. And could not find it. I almost wonder if I imagined it – except I didn’t.

This time (while attempting to retrace my steps) I arrived at an article with the title “Monkeys in Chinese Culture,” which informs me that, “Monkeys, particularly macaques and gibbons, have played significant roles in Chinese culture for over two thousand years.”

And, further, that Chinese deities were said to appear at times in the guise of monkeys, while many Chinese mythological creatures resembled monkeys or apes.

Now that would have been very useful when I approached writing the monkey scene in Devouring Light.

However, the notes on the pictograph proved fertile ground. I read of the various pronunciations for the word in Cantonese, Mandarin, Korean, and so on.

From them, I derived the names of my Simiae.

Old Jyutping, the chieftain, wise and earthy (despite his celestial nature) and indigo-furred.

Saru, who is nimble, beautiful, and clever – with fuschia fur.

Pinyin Hou enjoys riddles and sports a pelt of lime green.

Ko indulges in practical jokes, as well as the polar opposite: meditation. His fur is bright cyan.

All four are superb gymnasts and acrobats.

I wrote my scene. It remains one of my favorites! 😀

< For more about the world of Devouring Light, see:

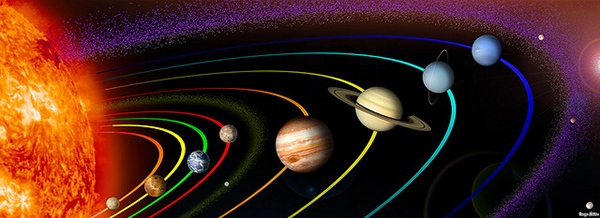

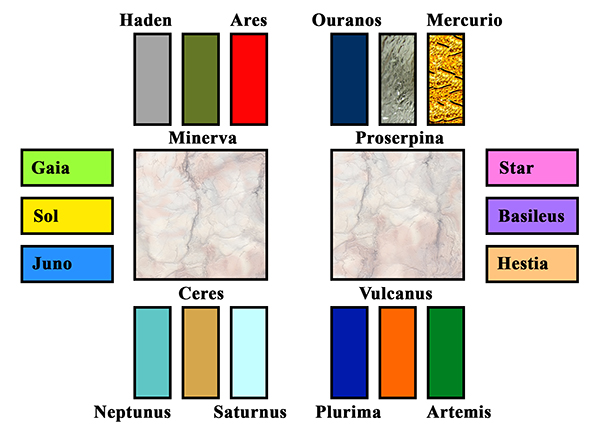

The Celestial Spheres of Sol

What Do Celestials Wear?

The Graces

Roman Dining

The Heliosphere

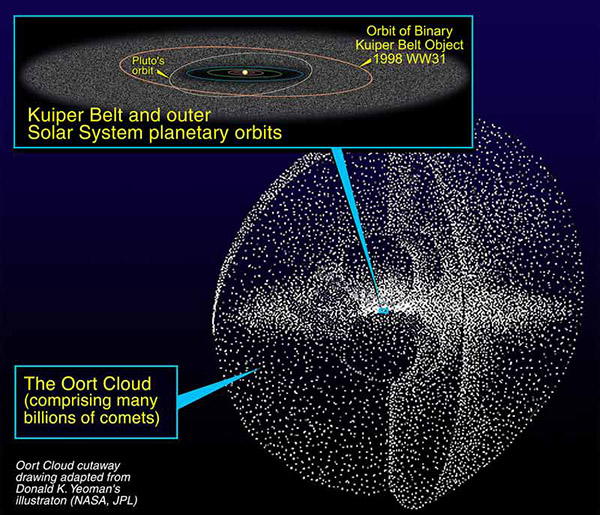

The Oort Cloud

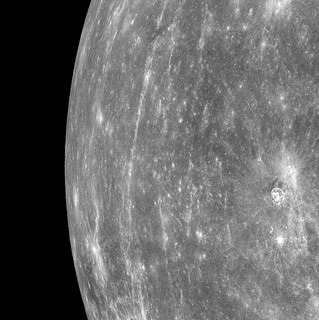

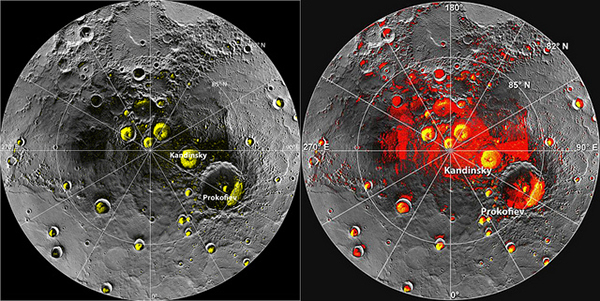

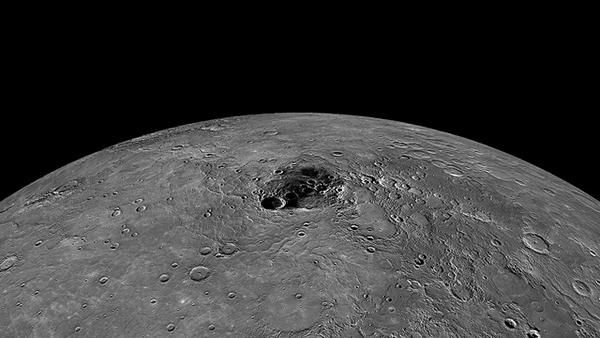

Mercury the Planet

Draco the Dragon