I love reading fantasy (as well as writing it), largely because of the sense of wonder and possibility it evokes. The journey through a strange and imaginary landscape feels magical. And that magic compels me.

I love reading fantasy (as well as writing it), largely because of the sense of wonder and possibility it evokes. The journey through a strange and imaginary landscape feels magical. And that magic compels me.

Yet setting isn’t enough. It’s the people and their doings – the story – that sustain my interest.

As a writer writing, finding the balance between story and setting can be tricky. My reader must understand enough to understand what’s at stake. Yet that necessary information mustn’t bury the protagonist and his or her very human concerns. It’s easy to err in either direction: presenting so much wonderful strangeness that the connection between reader and protagonist grows tenuous; or gliding over the setting so lightly that the protagonist’s challenges and desires seem obscure.

A brief aside . . .

Some readers prefer not to watch the sausage being made. If that describes you, this post may not be your cup of tea! I’m going to peer under the hood of one of my stories and discuss a revision prompted by my first reader’s feedback. For those of you who enjoy nothing better than seeing how an author does things, read on!

My first draft of Sarvet’s Wanderyar erred in the direction of flooding the reader with too much information about Sarvet’s culture. The women and men of the Hammarleedings live segregated from one another in sister-lodges and brother-lodges. This fundamental difference ripples through their entire society, their religious rituals, and their daily routines.

I dove right into those differences, and my first reader felt disoriented by it. The interesting thing to me was that the slight gap between heroine and reader didn’t manifest immediately. My reader cared about Sarvet, became invested in her wellbeing, and grew genuinely scared for her when Sarvet ran into danger. But when Sarvet encountered the crux of her dilemma – could she find the courage to confront and let go of the resistance within herself that shored up the external barriers she faced? – that was where my reader felt distance.

I dove right into those differences, and my first reader felt disoriented by it. The interesting thing to me was that the slight gap between heroine and reader didn’t manifest immediately. My reader cared about Sarvet, became invested in her wellbeing, and grew genuinely scared for her when Sarvet ran into danger. But when Sarvet encountered the crux of her dilemma – could she find the courage to confront and let go of the resistance within herself that shored up the external barriers she faced? – that was where my reader felt distance.

Not good!

I didn’t immediately know where I’d gone astray. I reviewed the climax scene. Had I failed to depict Sarvet’s dilemma fully? Did I not evoke her struggle to change vividly enough? Did I need to give more detail to her internal challenges? After re-reading the passage, I felt all that was present. And my reader agreed. She wasn’t really sure where the problem lay, what was provoking her sense of remove.

At that impasse, I was blessed with a flash of intuition.

The problem did not lie in the climactic scene itself. It occurred back at the very beginning. My reader was so preoccupied with understanding Sarvet’s milieu that she was distracted from forming a full bond with Sarvet herself.

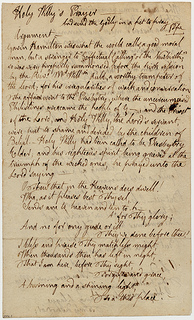

Along with my diagnosis of the problem came inspiration for how to fix it. I would give my reader two additional scenes that not only took us deep within Sarvet’s experience and showed us a pivotal part of her history, but that also included universal human experiences: enjoyment of a light-hearted holiday and the connection between a child and her father. Here they are . . .

But Other-joy was . . . complicated. Lodge-day was just fun. She’d spent it with her friend Amara last summer.

They’d greeted the men of Tukeva-lodge with traditional tossed thistle-silk streamers – a shower of crimson, gold, purple, amber, and blue pelted at the visitors as they approached the mother-lodge. Amara’s father was a bear of a man, big and round and laughing, with a pillow of a beard. His hello hugs swooped Amara, Amara’s mother Iteydet, Amara’s aunt Enna, and Sarvet off their feet. His arms felt like tree limbs. Flexible ones. Only after his enthusiastic civility did Feljas gaze in puzzlement at Sarvet’s face.

“But little Hilla never grew from belt high to chest high since Nerich!”

Amara broke into giggles. “Hilla’s picnicking with her best friend, mapah! This is my best friend, of course. Sarvet.”

“Then you’ll excuse a mapah’s zeal, little sister, won’t you? I thought you were mine!” His eyes twinkled.

Sarvet found herself giggling along with Amara. “Of course,” she answered. And knew a moment’s wistfulness. I wish he were my mapah. But Ivvar would never visit Kaunis-lodge, even on the greater fete-days like Other-joy.

Feljas was more like a wixting-brother than a father. He claimed the very tip of the valley-rock for their picnic blanket, teased Enna unmercifully about the damage her long eyelashes would do to the hearts of unlinked brothers, juggled their luncheon pears in fancy patterns before passing them to each sister for eating, dropped kisses on Iteydet’s cheek every fifth sentence, and pulled a sack of luxurious dried cherries from his capacious pocket for dessert. Then he fell asleep under Sarvet’s amazed gaze.

Her expression must have conveyed her astonishment, because Iteydet ventured a laughing explanation. “He’s always like this. Never stops until he really stops. In sleep. If I had to live with him day-in and day-out, like a sister, he’d wear on me.”

But Hammarleeding women didn’t live with their men. Sarvet had heard rumors that the Silmarish lowlanders did. Here in the mountains, sisters lived with sisters in the mother-lodges. And brothers lived with brothers in the father-lodges. As was proper.

Iteydet continued: “He’ll wake again soon. And I’ll be glad of it. It’s not a proper fete-day without Feljas’ jokes!”

He did wake. And proposed a game of tag combined with rolling down the mountain slope. Enna refused, but the sisters occupying three blankets near theirs were persuaded to join the fun, even including the normally staid Teraisa. Sarvet surprised herself when she abandoned keeping Enna company mere moments after her own plaintive refusal. Her limp was no disadvantage when rolling, not running, was the mode of movement.

The whole day had been like that: merry and easy and . . . loving. Would she trade Other-joy for Lodge-day? Yes! Well . . . maybe. Sarvet ducked her head down under the covers. No. Other-joy is special.

Sarvet still didn’t want to think about it. And yet she did.

What was her first experience of fathers? She didn’t really need to ask that question. She knew the answer. I’m just delaying. She’d been little, really little. How many years did I have then. Maybe five? It was one of her earliest memories. She was sitting in a clump of alpine flowers making a chain from the blooms, carefully selecting all the pink ones, when a shadow fell over her. She’d looked up to see . . . a father looming against the sky. He seemed as tall as the clouds, and his bearded face scared her.

“Sarvet?” His voice was gentle and his eyes kind.

He knelt so that she wouldn’t have to crane her neck to look at him. “Do you remember me?”

She didn’t, but her fear ebbed. He looked nice.

“I’m Ivvar, your mother’s linking-brother.”

She still didn’t remember him, but she held up her flower chain to show him. It was nearly done.

“Beautiful,” he told he. “Would you make one for me?”

And she did, a yellow one, not pink.

He’d just draped it around his neck and was thanking Sarvet when her mother arrived, hot and bothered and annoyed. “You shouldn’t be here,” Paiam declared.

“I’ve a right.” His voice was equable, but he stayed seated on the grass.

Paiam went on to argue with him. Sarvet couldn’t recall the words, but Paiam’s rage seemed to cover another feeling. She would have been crying, except that Paiam never cries.

Sarvet did remember the end of it. While Paiam stood by in fury, Ivvar had taken his daughter kindly in his arms and kissed her forehead. His lips were warm and dry. “Goodbye, little Sarvet. I’ll love you forever.”

“You’re going?” He’d been a fun play fellow. It seemed a shame to lose him just when she’d found him.

“Yes, I’ll be living at Rakas, not Tukeva, now. The brothers of Rakas visit a different mother-lodge.”

“Oh.” She’d been placid then, accepting his farewell. Now . . . now she felt differently. Paiam drove him away, shun her! I could have been like Amara and Brionne, seeing my own father several times each year, if it hadn’t been for her. With a small shake of her shoulders, Sarvet opened her eyes.

Her mother was seated on the bench in front of her, a little to the right. She had the same expression on her face that Sarvet felt leaving her own features: faint distaste mingled with longing. Sarvet winced. I don’t want to be like her. She looked away.

Did my revision do what I wanted? Would my reader walk more fully in Sarvet’s boots? That was the question, indeed. I sent the revised manuscript off to my first reader and waited with baited breath.

Did my revision do what I wanted? Would my reader walk more fully in Sarvet’s boots? That was the question, indeed. I sent the revised manuscript off to my first reader and waited with baited breath.

Her answer: a resounding yes! She’d experienced no sense of distance at all, feeling thoroughly there as Sarvet confronted her destiny.

Yay!

My reader did suggest one other minor change. I’d made Sarvet a bit on the young side for the story that emerged. She needed to be closing on 16, rather than 14 approaching 15. Plus there were a few more typos to correct. But in all essentials my story was complete.

I’d learned once again how important a first reader is to my process. I’m too close to my story to always perceive how it touches my readers. I need one of them to report back from the reading front!

I also learned that an error at the story’s beginning may hide for an interval, manifesting only in a later passage. Who would have guessed? I love these unexpected revelations, whether they’re within a story or outside one. This is why I write!

For more about the writing experience, see:

The First Lines

Writer’s Journey