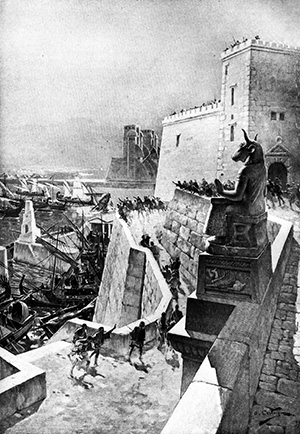

The ancient Phoenicians were seafarers, and they created the first real maritime civilization in the Mediterranean Sea around 1550 BC.

The ancient Phoenicians were seafarers, and they created the first real maritime civilization in the Mediterranean Sea around 1550 BC.

The ancient Egyptians had mounted various sea expeditions earlier, but the Phoenicians established regular trade routes between their numerous city-states, from Tyre in the east to Tingis in the west on the Strait of Gibraltar, and everywhere in between.

Thus the Phoenicians were the first to develop truly sturdy, seaworthy ships and all the arts that go with shipbuilding and sailing. The later Mediterranean civilizations learned from the Phoenicians, and individual sea captains recognized the Phoenicians – even after their dominance faded – as masters of the sea.

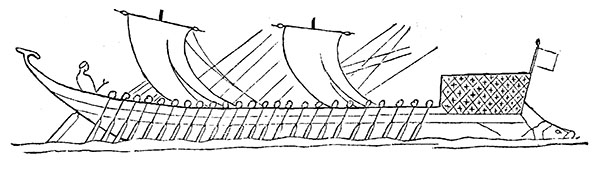

The first warships – needed to protect the sea routes – were slim craft with a shallow draft and propelled by oarsmen, but possessing a sail to take advantage of favorable winds when possible. The ancient Greeks named these warcraft for the number of oars propelling the vessel.

Thus the early 30-oared warship (15 on each side) was the triaconter, from triakontoroi or “thirty-oars.”

And the later 50-oared warship (25 on each side) was the penteconter, from pentekontoroi or “fifty-oars.”

By the time of my novel Fate’s Door (352 BC – 329 BC), warship technology had advanced considerably. The early warships served more as fighting platforms for the warriors, who would seek to board an enemy ship and subdue its warriors in man-to-man combat. Later warships had catapults aboard for assaulting the enemy with missiles. Even more important, their prows possessed bronze-clad rams for ramming enemy ships and sinking them.

This meant that swift maneuvering was essential, as well as increased power and speed. The only way to get that was by adding more oars to the ship. And the best way to add oars was to add another bank of oars, one bank of rowers on a lower level and another bank of rowers on an upper level.

These double-banked warships were soon made obsolete by triple-banked warships. The ancient Romans called them triremes, and that is the name we modern folk use as well. But the ancient Greeks called them triereis or, in the singular, a trieres, literally meaning “three-rower.”

These were peerless warships, and the ancient Greek city-states built fleets of them, cementing the Hellene domination of the Mediterranean Sea.

As history unfolded, the desire for ever more powerful ships grew. Adding a fourth bank of oars was impractical, but adding another man to each oar was not. When the extra man sat on the top bench, the ship was known as a tetreres or “four-rower.”

When one extra man sat on the top bench and another extra man sat on the middle bench, the ship was a penteres or “five-rower.” At the time of Fate’s Door, the penteres was a new development. Most fleets had but one, and it was the flagship of the fleet.

Altairos boasts to Nerine (the protagonist of Fate’s Door) that each of his father’s warfleets has at least one penteres, reassuring her that he will not be in danger when he accompanies the fleets to challenge the pirates preying on their trade ships.

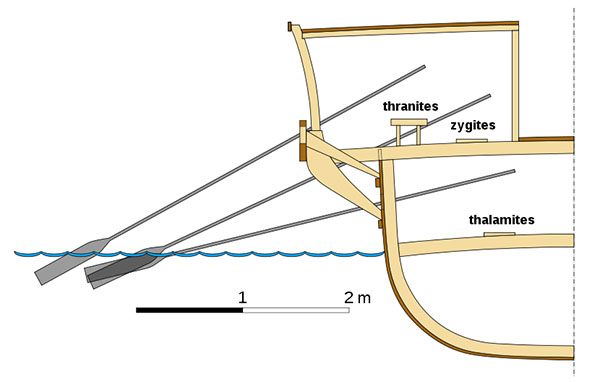

The diagram above shows the rowing arrangement for a trieres. One thranites sat on the top bench with his oar passing through a lock in the side of the projecting outrigger of the ship.

One zygites sat on a middle bench, recessed into the deck, with his oar passing through a lock in the floor of the outrigger.

And one thalamites sat on the lowest bench with his oar passing through a lock in the side of the ship.

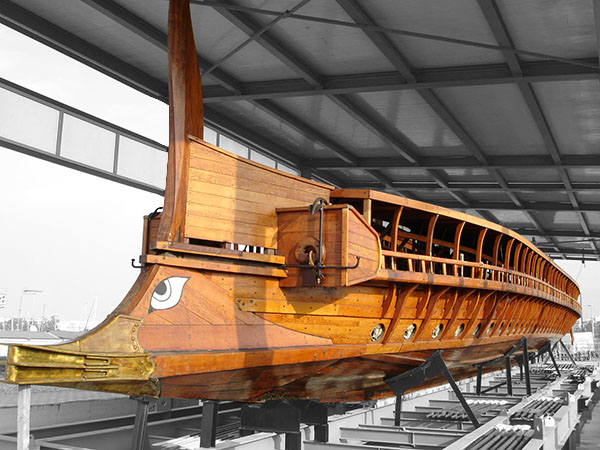

In 1985, the reconstruction of an ancient trireme was started by a shipbuilder in Piraeus, using drawings by naval architect John F. Coates. Coates developed his drawings through long consultation with historian J.S. Morrison.

In 1987, the Olympias was launched and put to sea trials. In the most successful of these, the ship achieved a speed of 9 knots (10 mph or 17 km/h). It was able to execute 180-degree turns in less than 60 seconds and within an arc of two and a half ship-lengths.

Given that this maneuverability was achieved with an inexperienced crew of volunteers, there was reason for the enthusiasm of the ancients for the trireme. It was indeed the “Dreadnought of the Mediterranean.”

For more about the world of Fate’s Door, see:

Ground Looms

Lapadoússa, an isle of Pelagie

Merchant Ships of the Ancient Mediterranean

Garb of the Sea People

Measurement in Ancient Greece

Horse Sandals and the 4th Century BC

Knossos, Model for Altairos’ Home

For more about the Olympias, see:

The Olympias on Wikipedia

The Trireme Trust, dedicated to disseminating information about the Olympias

The Sea Trials of the Olympias on YouTube

Which all makes me incredibly curious what system was in place when an oarsman died or got wounded – how tangled did the other oars get? Could the affected oar be dumped?

I remember something like that in the epic film Ben Hur. I also recall the oarsmen were chained to their posts (maybe only if they were slaves? were they all slaves?) so they wouldn’t go anywhere – and of course went down with the ship – in the middle of battle.

The communication system there was a drum-beating director – it would be interesting to know how the instructions were given for quick turns.

Now you’ve got me curious about the system used by the ancient Romans. 😀 Did they use slaves to row their triremes?

The ancient Greeks did not. In fact, in an emergency, when more rowers were desperately needed, slaves were deliberately freed before being employed as oarsmen.

However, quarters were very tight aboard a warship. The oarsmen had to board and disembark in a specific order to prevent complete chaos during the procedure. If the ship was rammed and damaged enough to sink, few escaped its confines in the confusion. Drowning was a common fate for the rowers, even though they were not chained to their posts.

A piper playing an aulos ensured the rowers kept the proper time, which varied according to the maneuvers being performed.

An article on Wikipedia about the trireme gives more of these details.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trireme