In the 4th century BC, a well-established trade route led from the Aegean Sea across Europe to the southern shore of the Baltic Sea. It was called the Amber Road, because amber washed up on the beaches of the Baltic was brought south along it to the Mediterranean civilizations, where that substance was greatly prized.

The route was not a nicely paved continuous road, of course. Rather it was an established route through the terrain that avoided difficult mountains and hostile peoples, and likely included arrangements with friendly tribes for the purchase of shelter, food for the traders, and fodder for the horses.

One route postulated for the Amber Road connects Italy to the Baltic, but it probably came into use during the dominance of the ancient Romans. My story, Fate’s Door, takes places when the Hellenes were more influential, as well as ancient Persia and other city-states in the eastern Mediterranean.

Additionally, there were established trade routes north from the Aegean following the Vardar River and then the Great Morava River to the Danube.

Additionally, there were established trade routes north from the Aegean following the Vardar River and then the Great Morava River to the Danube.

From the Danube, the River Tisza leads up to the Carpathian Mountains, a relatively gentle, non-alpine series of ridges. The Vistula River flows from the Carpathians to the Baltic, providing a simple last leg of the journey north.

This is the route I envision my heroine Nerine following when she travels with her escort of guards across Europe.

Not all the rivers or all portions of the rivers are navigable by boat, so I have the group riding along roads and paths beside the rivers. Indeed, the Keltoi living in central Europe at the time were famous for their network of roads and the trade that passed along them.

Because the route follows the Vardar from its mouth to its source, and the Great Morava from its source to its mouth, I reasoned that Nerine and her guard would find places near the sources of these streams where the water was relatively shallow and safe to ford. The same could be said of the Tisza and the Vistula.

This was an important point, because the ancient Hellenes focused more on travel by sea than travel by land, and were not the great bridge and aqueduct builders that the ancient Romans were.

The Danube River gave me serious pause. Clearly, since amber was regularly traded during this time (and before), the ancient traders possessed a way to cross the Danube. But there would be no fording it or wading it. How would they get themselves, their supplies, and their trade goods to the other bank?

Nerine comments that the Danube must more than 4 stadia wide when she first sees it. That is, more than half a mile, or close to a kilometer, from bank to bank.

I researched river boats in the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, and discovered that the peoples of central Europe had them and made extensive use of them for both fishing and river trade.

But what were these boats like? Could they have carried the horses of traders (or those of Nerine and her escort) across the Danube?

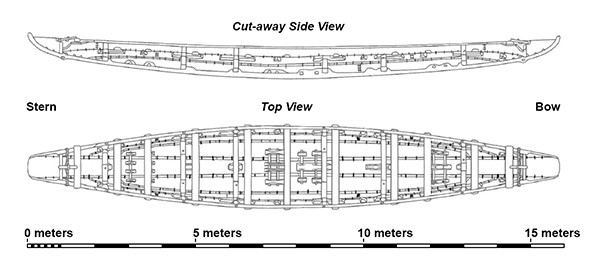

Luckily for me, a group of experimental archaeologists decided to construct a “sewn-plank” boat from the Bronze Age. It was a sea-going vessel, but seemed a reasonable proto-type for the boats the Keltoi may have plied on the Danube and the navigable reaches of the Great Morava and other rivers, for trade and for hunting the vast sturgeon that swam those waters on the cusp between pre-history and history.

Their boats were no mere hollowed-out tree trunks, but skillfully constructed vessels using thick planks, an intricate system of cleats and slots to fit the timbers together, and “ropes” of yew withies, passed through holes in the wood and knotted to bind the planks together.

Moss was used to fill the seams between the planks, and beeswax to seal the yew withy “stitches.” The video below shows how these stitches were made.

The experimental archaeologists were successful in their project, and they used authentic tools and methods in their building of the Morgawr. The news coverage of the boat’s launch calls it a shaky maiden voyage, but I believe they were taking some journalist license to gain an attention-catching headline. The Morgawr was expected to ship water until the timbers swelled and shut the inevitable leaks.

These sewn-plank boats were large, roughly 50 feet long (16 meters) and 8 feet wide (2.5 meters).

But, but, but!

Their method of construction meant that the bottom was chock full of blocky cleats. As I stared at the photo, I couldn’t imagine a horse stepping into the vessel easily and then standing there patiently on the uneven footing, while the boat swayed and moved on the water.

Nerine, her guards, and their material goods could cross the river in these boats. I would have to find another way for the horses. Could they swim?

The first thing that came to mind were the ponies of Assateague Island off the coast of Virginia in the United States. The ponies are tough and semi-wild. And every year in the summer, they are rounded up to swim across the sea channel between Assateague Island and Chincoteague Island.

How wide was this channel? And how long did it take the ponies to swim it?

That information was readily found. The channel is roughly half a mile across and it takes about 4 minutes for a pony to swim it.

The mounts of the ancient Greeks were small and tough, like the Chincoteague ponies, closer to the primitive horse than the highly bred horses of our modern era. They had black manes, tails, and legs. Their body color was golden brown with a black stripe along the back from the neck to the tail.

It seemed clear that just as the Chincoteague ponies could swim the Assateague Channel, so the horses of Nerine’s cohort could swim the Danube.

I had found the way for Nerine, the Poniró Peltastés (Nerine’s escort guards), their supplies, and their mounts to cross the Danube.

But the Danube is a mighty river with the powerful current that a large roil of water produces. Adventure awaits those who dare its dynamic flow! 😀

For more about Nerine’s world, see:

Vertical Looms

Names in Ancient Greece

Warships of the Ancient Mediterranean

Calendar of the Ancient Mediterranean

Ground Looms

Lapadoússa, an isle of Pelagie

Merchant Ships of the Ancient Mediterranean

Garb of the Sea People

For more about sewn-plank boats, see:

Noth Ferriby’s Bronze Age Boats

The Ferriby Boats

The Morgawr

For more about the primitive horse, see:

The Polish Primitive Horse

The Mongolian Wild Horse

For more about the Chincoteague ponies, see:

The Chincoteague Pony

Assateague Island National Seashore

Chincoteague Island Pony Swim

Wow – that is a lot of fine detective work! Completely believable, too. Maybe the humans crossed in the boat, with the horses swimming along sometimes.

We take so many things for granted – but they had no way to build a half-mile bridge.

So true about one’s tendency to take basic conveniences of modern life for granted. 😀

The ancient Romans built many feats of engineering in service of transportation, but the ancient Greeks simply took to the seas, rather than fighting their rugged, mountainous land.