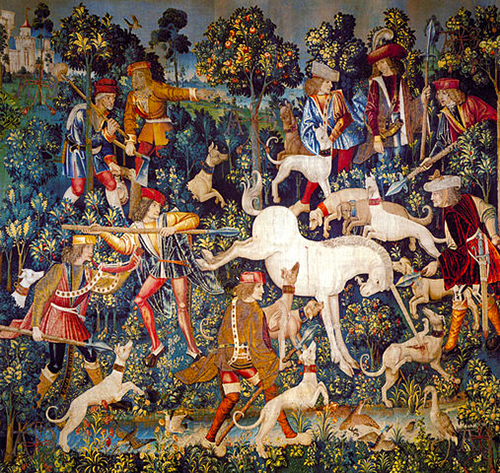

The huntsmen in the medieval tapestries depicting the unicorn hunt are clearly hunting par force or by coursing. Meaning that they use sighthounds, not only scent hounds, to pursue the prey.

In the fourth tapestry of the unicorn cycle, the dogs and the huntsman have caught up with the unicorn, but to little avail. The beast is fierce and fights off its attackers successfully. Its horn pierces one hound’s breast, likely killing it. Who knows what further wounds the unicorn inflicts before it charges away through the forest?

In order to write my short story, The Hunt of the Unicorn, I needed to learn more about coursing as it was done in medieval times.

Fortunately, there are several books from the time period detailing exactly how the hunt proceeded. And I found a modern-day enthusiast who devotes a website to the topic.

The “Great Hunt” of the Middle Ages was an elaborate affair with distinct and multiple stages.

The day before the hunt, the huntmaster sallies forth to talk with foresters and woodsmen.

From them he learns what game is available and where each beast lay overnight. He hears accounts of what the foresters know regarding the probable size of the animal. The noblemen participating in the hunt want a large, strong adversary.

The whole of the hunting party sets out the next day: noblemen, huntmaster, huntsmen, dog handlers (berners), mews boys, etc.

While the noblemen enjoy an al fresco meal, the huntmaster sends his huntsmen out to the lays he learned of the day before. There each huntsman records the size of the animal’s hoofprint by breaking a small stick and collects the fumes (droppings).

The huntsmen bring their sticks and fumes back to the huntmaster, who evaluates them to determine the potential prey, one that is large and ‘in fat.’

The huntmaster chooses which beast they will hunt, and that focuses their attention. They will not break off from pursuit of that animal to chase another.

Once the prey is chosen, three relays of three sighthounds, each relay accompanied by a berner, are placed along the probable route that the pursuit will take.

Then a special tracking dog called a lymer is set to work. (He is a scent hound, not a sighthound.) It is his job to find and move the prey animal. He works on a leash or ‘line’ held by his keeper.

Once the prey has been located and moved to the start of the planned route, the hunt proper begins.

Twelve or twenty-four scent hounds called raches are loosed to chase the prey, exhausting it both through the length of its running flight and through the fear induced by the baying of the dogs.

The noblemen follow on horseback, at times wounding the prey animal with their swords or spears. Bows and arrows are not used.

If the raches lose the scent, the lymer is brought forward again to locate and move the prey.

As the hunt draws past the first relay of sighthounds, these dogs are released. They are very fast, very strong, and fierce fighters. They sprint to bring the prey animal down.

But, often, the prey is equally fast, equally strong, and equally fierce. It escapes. Or it fights successfully and then escapes.

(This is the moment depicted in the fourth tapestry shown at the beginning of this post.)

So the hunt goes onward in pursuit. And when they pass the next relay of sighthounds, this second relay is loosed.

In the medieval myth about the unicorn, the huntsmen and their hounds cannot succeed. The unicorn is too fierce for them. It is only by the involvement of a maiden that the fabulous beast can be subdued.

But most hunts of hares, deer, or even boar could succeed. If the first relay of sighthounds did not pull the prey down, then the second or third would.

The dogs were not allowed to kill the animal. They were pulled off, and one of the noblemen would slay the beast with his sword, dagger, or spear.

The animal would be skinned and disemboweled, the dogs given their share, and the remainder sent to the castle kitchens to be made into dishes for feasting.

All of the above likely seems brutal to our modern sensibilities. We can imagine rather vividly what it might be like to be the prey animal suffering a chase to its death.

But the medieval hunters were the culmination of a long history of hunting and coursing—millennia—to provide for the table. Without hunting, there was not enough food for them or their families. And like humans will in every time and place when a job has to be done, they made it serve as entertainment as well.

Many nations in our modern world have outlawed coursing, deeming it cruel and inhumane.

Lure coursing, in which a mechanically operated artificial lure is ‘hunted,’ keeps alive some of the pageantry and tradition of the medieval hunt, and the specially bred skills of the magnificent sighthounds, without putting an innocent prey animal through torture.

For more about the Hunt of the Unicorn, see:

The Hunters Enter the Woods

The Unicorn Is Found

The Unicorn Is Attacked

The Mystic Capture of the Unicorn

The Unicorn Is Killed

The Unicorn Lives

Unicorn’s Lullaby