In the seventh tapestry of the unicorn cycle, we see the unicorn resurrected and contentedly lying beneath a tree full of pomegranates.

The imagery has departed from the great hunt as medieval nobles knew it to become entirely allegorical.

The hunter is Love, the hunted game is the poet-lover, and the happy conclusion of the hunt is the union between the two.

Jehan Acart de Hesdin wrote a poem of 1900+ verses in 1332—La Prise Amoureuse—in which he speaks of the forest as Youth and the huntsman’s hounds as Beauty, Kindness, Intelligence, Courtesy, and so on.

Although the unicorn is both tethered and fenced, we know that he could easily break his leash and leap the low fence. He stays because he chooses to.

The plants in the tapestry symbolize different elements of loving commitment.

Ripe, seed-laden pomegranates were a medieval signifier for fertility and marriage. Wild orchid, bistort, and thistle possess similar symbolism.

The flowery meadow adorning so much of this tapestry is one of the things I love most.

It is a style known as millefleurs (“a thousand flowers”) that was used only in the late European Middle Ages, principally between 1480 and 1520. The plants are of many different varieties, and they fill the ground randomly, without pattern and without connecting or overlapping.

Later tapestries would feature repeats of a smaller number of different plants, usually placed as mirror images of one another.

When the millefleurs style was revived in the nineteenth century by William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites, the plants often overlapped and appeared as part of the landscape rather than as an ornamental backdrop.

I was utterly charmed when I encountered a millefleurs-inspired garden in the book Theme Gardens by Barbara Damrosch. She describes a plesaunce—a lawn in which the grass has been replaced by low-growing flowering plants such as creeping thyme, catmint, primroses, pinks, violets, and more.

For a while I dreamed of planting just such a garden in my own yard. Then my twins were born, and gardening took a backseat to mothering my children.

But I did include that plesaunce in one scene near the end of my short story The Hunt of the Unicorn. The princess awaits her huntsmen in a walled garden with tall delphiniums and foxgloves along its edges and a flowery mead at the center.

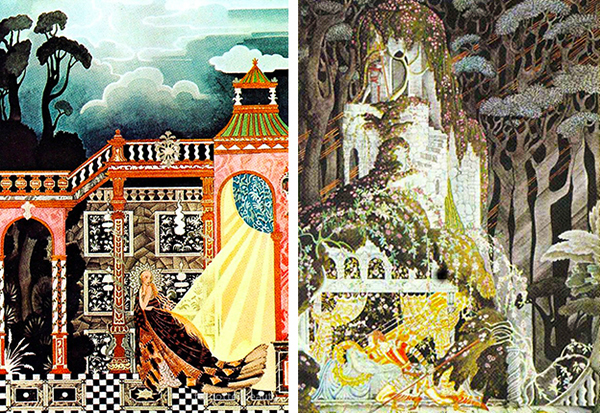

Another scene near the beginning of my story was also inspired by art. The princess walks through the halls of an Escher-like palace with more stairs than makes sense, and more passageways than chambers. But the palace resembles the vibrant structures in two illustrations by Kay Nielsen, more than the terrifying spaces depicted by M.C. Escher.

I didn’t even remember the Nielsen paintings until after I wrote the scene, when I had the nagging sensation that my palace was strangely familiar.

I had to do quite a bit of searching to find them, but find them I did! One illustrated the fairy tale “Catskin” and the other, the fairy tale “Rosebud,” both from Hansel and Gretel and Other Stories by the Brothers Grimm.

For more about the Hunt of the Unicorn, see:

The Hunters Enter the Woods

The Unicorn Is Found

The Unicorn Is Attacked

The Unicorn Defends Itself

The Mystic Capture of the Unicorn

The Unicorn Is Killed

Unicorn’s Lullaby