When Nerine, the sea nymph protagonist of Fate’s Door, traveled across Europe in the 4th century BC, I needed to know who she would encounter on her journey.

The first part of her route along the Vardar through Macedonia (Paionía) was fairly simple. (The river was called the Bardarios then.) The Paíones living there had adopted the customs of their Hellene neighbors. Their architecture and dress were similar. They were said by the people of the time to be tougher and more hard-working than the southerners, that quality being the main difference between them.

The Keltoi of central Europe required more research, but there is a lot of information about these proto-Celts.

After Nerine crossed the Carpathian Mountains, she entered the lands of the Gutones. The information on the Gutones is much scarcer than I would have preferred.

The Gutones lived in Poland along the Vistula River (the Istula, according to the ancient Greeks) and on the coast of the Baltic Sea. Early historians spoke of them as migrating south from Scandia (Sweden).

There are three potential spots discussed by more modern historians as origination points.

Götaland, or Gothland, a southeastern region of Sweden, provides a likely homeland for the ancient Goths. Equally possible are the lands along the river called Göta älv (the River of the Geats). And then there is the island named Gotland.

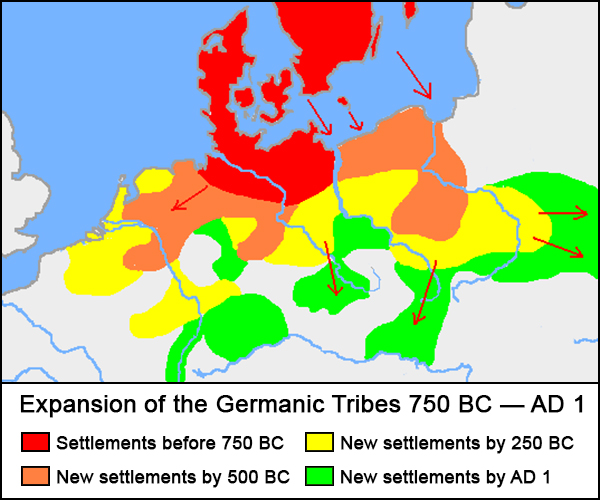

There seems to be no definitive answer, but what is certain is that these Scandinavian tribes arrived in Poland sometime before 750 BC and slowly spread southward and eastward, eventually arriving on the shores of the Black Sea.

Jordanes, a historian of ancient Rome in the 6th century AD, wrote a comprehensive account of the Goths. He possessed Gothic ancestry and was eager to show that Goths came of a past as glorious as that of the Romans, so one must assume that some of his narrative is fictional. And in any case, his description of Gothic culture concerns the Goths of his time, rather than the Gutones of Nerine’s time, some thousand years earlier.

Today’s historians think that the Goths (or Gutes or Geats or Gutones – the ancients had many variants) did not come south and overwhelm the existing peoples living in northern Poland, but simply settled there peaceably, slowly assimilating their culture, as well as influencing it.

As the map above shows, by 334 BC (the year of Nerine’s journey), the Gutones had expanded their reach from the shore of the Baltic Sea along the Vistula River. I chose the island Gotland as their original homeland, and then started researching the Przeworsk culture of the people with whom the Gutones mingled.

(The ancient Greeks used the term Gutones for the Goths, and thus I chose their term, rather than any of the other many variants.)

(The ancient Greeks used the term Gutones for the Goths, and thus I chose their term, rather than any of the other many variants.)

The Przeworsk peoples, and thus – likely – the Gutones as well, lived in small, unprotected villages of just a few houses and with a population of only a few dozen. They knew the technology for digging and building wells, so they did not have to live near water, but the Vistula River would have served as a natural conduit for trade.

Their houses were fashioned from logs and were usually set partially below ground level.

The one photograph I could find – of a museum display – showed the people wearing more solid-colored clothing than the Keltoi, although the lady of the pair sports a skirt of “window-pane” plaid, while the gent possesses a more complex variant on the same pattern on his mantle.

The one photograph I could find – of a museum display – showed the people wearing more solid-colored clothing than the Keltoi, although the lady of the pair sports a skirt of “window-pane” plaid, while the gent possesses a more complex variant on the same pattern on his mantle.

I did find mention of colorful straps created by tablet weaving which were used to make straps and belts, and to edge garments. I also discovered that archeological evidence indicated that nearly every individual among the Gutones carried a comb in a pouch on his or her person and used it frequently to keep his or her long hair – worn loose or with the front locks pulled back in a bun – tangle free.

Taking all this and swirling it in my imagination, I came up with a peaceable people with a calm and disciplined character, practical and much less fiery than the Keltoi living south of the Carpathians.

The people of the Przeworsk culture followed a tradition of erecting circles of standing stones, and these were used to conduct general assemblies in which decisions affecting the whole village or several villages were made.

The people of the Przeworsk culture followed a tradition of erecting circles of standing stones, and these were used to conduct general assemblies in which decisions affecting the whole village or several villages were made.

The northerners from Scandia evidently possessed this tradition as well. They also shared the practice of erecting lone standing stones or menhirs.

But the purpose such stones served is much debated. Were they used in rites of sacrifice? Were they territorial markers? Were they elements of a complex ideology? Did they mark graves? Did they commemorate great heroes?

But the purpose such stones served is much debated. Were they used in rites of sacrifice? Were they territorial markers? Were they elements of a complex ideology? Did they mark graves? Did they commemorate great heroes?

The later seems to have been part of the Scandinavian tradition. But I could find no definitive answer for the standing stones of Poland, merely that they form a remarkable part of the landscape.

One tradition the Gutones brought with them from the north was the burial mound. The Przeworsk culture before them cremated their dead, placed the ashes in an urn, and then buried the urn in a cemetary. The Gutones also favored cremation – although their funerary rites were not uniform – but they placed jewelry, glassware, pottery, fibulae, and their characteristic bone combs within the mound erected over the ashes of the dead.

Sometimes a standing stone was placed atop the burial mound; sometimes a ring of them encircled it. When Nerine descends from the Carpathians, her first encounter with the culture of the Gutones is the sight of a burial mound in the forested foothills. Although, the season is autumn for Nerine, and the leaves of the beech trees, golden.

Sometimes a standing stone was placed atop the burial mound; sometimes a ring of them encircled it. When Nerine descends from the Carpathians, her first encounter with the culture of the Gutones is the sight of a burial mound in the forested foothills. Although, the season is autumn for Nerine, and the leaves of the beech trees, golden.

For more about the world of Fate’s Door, see:

Crossing the Danube

The Keltoi of Európi

Vertical Looms

Names in Ancient Greece

Warships of the Ancient Mediterranean

Calendar of the Ancient Mediterranean

Ground Looms

Lapadoússa, an isle of Pelagie