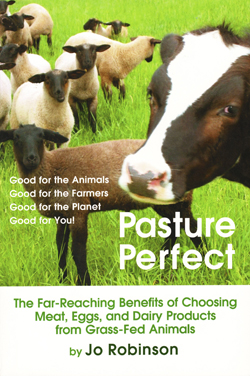

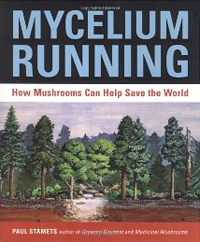

First, a confession: I didn’t read every page of Mycelium Running. I didn’t even read most of them! So why am I telling you about this book? The half of it I did read was amazing. But let me explain.

First, a confession: I didn’t read every page of Mycelium Running. I didn’t even read most of them! So why am I telling you about this book? The half of it I did read was amazing. But let me explain.

Mycelium Running is a manual geared toward practicalities, toward getting out there and getting your hands dirty. If you need to know how to heal an ailing forest under your care, how to purify bacteria-laden water running off your land, or how to restore your compacted and abused back yard, then Paul Stamets’ book will tell you exactly what you need to know.

But I’m not quite ready for action. I do hope to tackle my clay-imbued and weed-strewn garden over the next few years, but I’ve got other projects ahead of that one on my to-do list. Mostly I’m gathering facts, seeking to understand the big picture. And Mycelium Running is good for that too – especially the earlier chapters. Thus I dare bring it to your attention.

The basic facts of mycelium are fascinating. And the scope of its influence and potential are far beyond anything I might have imagined. Frankly, before I read Mycelium Running, I hadn’t thought much about mushrooms. I loved eating them sautéed in butter. I enjoyed spotting them during August nature walks. And I took pleasure in whimsical paintings featuring fey dancers amidst mushroom circles. Essentially, I was ignorant!

Which meant I loved the experience of having my eyes opened. (Yes, nothing like tickling my curiosity!)

But what is mycelium anyway? The dictionary names it the vegetative part of a fungus. It consists of a mass of branching, thread-like filaments called hyphae. Healthy soils harbor colonies of mycelia, but tree bark or fallen leaves or your compost heap (if, cool) also feed mycelial or fungal mats.

Fungi eat by secreting acids and enzymes into their surroundings and then absorbing the created nutrients through the cells of their mycelia.

The mushrooms we notice springing from a forest floor or among the grass blades of a lawn are almost a side show of the drama hidden below ground. That’s where the real action transpires. Spores released from a mushroom (the fruiting body of the fungus) germinate like plant seeds when they encounter the right moisture, temperature, and nutrients. From microscopic grains, they grow and branch, and grow and branch, creating a mycelial mat. Mycelial mats vary in size. The one supporting the health of a birch tree in your front yard might be just a few feet across. But one mycelium in eastern Oregon – Armillaria or honey mushroom – once covered 2,400 acres!

But more than just odd trivia make mycelia cool. In fact, I can’t confine myself to just three cool things. Here are six!

Mycelia Partner Plants

Most plants – from grasses to Douglas firs – have mycorrhizal mycelia as partners. These mycelia form sheaths around the plant roots and bring nutrients and moisture to the host plant, spreading a net far wider than the roots alone could do. And actively creating nutrients with the action of its enzymes and acids.

Plants with mycorrhizal partners thrive, growing faster and stronger than those without, and resisting diseases better. Their root masses are larger and denser. Their stems or trunks are thicker and taller. Their branches are leafier. The difference is dramatic. And some plants won’t grow at all without their attendant mycelia.

Mycellium is Nature’s Internet

The physical structure of mycelia shares the branching architecture of neural pathways in the mammalian brain. It also mirrors diagrams of the internet’s information-sharing systems. Mycelia might very well be the feedback loop by which planet Earth regulates its ecosystems. They certainly respond in complex ways to complex environments.

In one experiment, researchers mapped the flow of nutrients via mycellium between a Douglas fir, a paper birch, and a western red cedar. The researchers covered the fir, simulating deep shade. The mycellium responded by channeling sugars from the root zone of the birch to the root zone of the fir (which was unable to photosynthesize the sugars it needed).

Outside the lab, mycelia build soil, remove contaminants such as spilled diesel fuel, and filter bacteria out of polluted water.

Could mycelia possess a form of intelligence never envisioned by humans? Impossible to say at this point in history, but the biochemical connections formed by mycelia surpass those of supercomputers. And the organisms display nuanced responses to the world around them. Perhaps our next generation of computers will use fungi instead of copper micro-wire for hardware.

Even Parasites Bring Benefit

The most famous parasitic mushroom, Armillaria or the honey mushroom, is stigmatized as a blight. It can destroy thousands of acres of forest and is banned in many areas. But look again, and look longer. Parasitic fungi may serve to select the strongest plants for survival and to repair damaged habitats. Each time Armillaria swept through that 2,400-acre spot in Oregon, it created nurse logs for more directly benign fungi, it increased soil depth, and it covered barren rock with rich humus. The stage was set for a vibrant revival of habitats and ecosystems.

Mushrooms Lead Eco-restoration

Consider forest fires. The first species to appear amidst the ash and cinders are mushrooms – typically morels and cup fungi. They’re fast-growing and quick to decompose. As they mature and release spores, they also emit fragrances that attract insects and mammals. The insects attract birds, and all these newcomers bring seeds with them. Soon the wasteland burgeons with life – all starting with fungi.

Timber Is Not a Renewable Resource

The old growth forests of the Pacific Northwest accessible to loggers are largely gone. The first two replantings of logged areas are gone as well. Logging companies are now harvesting the third. But no one is making plans for a fourth replanting. Why? With each clear cut, the mycelia of the forest is damaged and the soil grows both thinner and poorer. You can’t get good wood from trees growing in exhausted soils, so many logging companies are selling their land.

Mushrooms Are Renewable

Now consider another patch of forest, this one in south central Oregon. Imagine harvesting timber from it. You’d get a substantial financial return, but eventually you’d reach the end of what you could profitably extract. When you were done, the land would be effectively barren.

But what if you harvested matsutake mushrooms – tasty and desirable – instead? The economic benefit would equal that of the timber (actual calculations have been done), but each year you’d also get thicker soils, reduced erosion, increased stream health, greater biodiversity, improving air quality, and increased regional cooling. And it can go on forever.

I’ll take it!

And do I recommend this book?

I do.

Just don’t try to read it from cover to cover. Begin with part one, where the big picture info is dense. As technicalities creep in, start skipping a bit. Part two held my interest. Part three is where I touched down lightly. (I’m not ready for mushrooms species specifics yet!)

I’m normally a cover-to-cover reader, but this book was worth adjusting my reading style for. It changed my world view. Again! Give it a try. It might change yours!

Mycelium Running at Amazon

Mycelium Running at B&N

For more green living concepts, see:

Permaculture Gardening

Green Housekeeping

Grass Green

For more cool science trivia, see:

Water

Before my toiletries revelation, I’d been using a generic version of Cetaphil® Gentle Cleanser. It worked well. The Gentle Cleanser kept my face clean without drying my skin. Perfect! Until I checked the EWG Skin Deep® Cosmetics Database.

Before my toiletries revelation, I’d been using a generic version of Cetaphil® Gentle Cleanser. It worked well. The Gentle Cleanser kept my face clean without drying my skin. Perfect! Until I checked the EWG Skin Deep® Cosmetics Database. I tried using Aubrey® Organics Rosa Mosqueta® Bath & Shower Gel, but my cheeks developed a bit of red chapping in response. Plus I had concerns about the grapefruit seed preservative in it. Grapefruit seed extract may be contaminated by triclosan and methyl paraben or benzethonium chloride, unless it is processed properly.

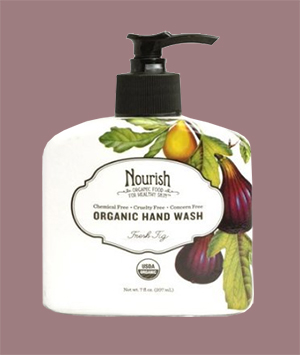

I tried using Aubrey® Organics Rosa Mosqueta® Bath & Shower Gel, but my cheeks developed a bit of red chapping in response. Plus I had concerns about the grapefruit seed preservative in it. Grapefruit seed extract may be contaminated by triclosan and methyl paraben or benzethonium chloride, unless it is processed properly. And then I found myself away from home during a family medical emergency. The hand soap in the house where I stayed ran out. I dashed to the local health food store and picked up a bottle of Nourish Organic Hand Wash. The ingredients looked good, but I didn’t think more about it until after my family member in the hospital was out of danger.

And then I found myself away from home during a family medical emergency. The hand soap in the house where I stayed ran out. I dashed to the local health food store and picked up a bottle of Nourish Organic Hand Wash. The ingredients looked good, but I didn’t think more about it until after my family member in the hospital was out of danger. At this point, I’ve only been using Nourish for a few weeks. I’ll report back in a few months to share how it holds up over the long haul. I’m hopeful! 😀

At this point, I’ve only been using Nourish for a few weeks. I’ll report back in a few months to share how it holds up over the long haul. I’m hopeful! 😀