Mother Holle (or Frau Holle) is one of the stories collected by the Brothers Grimm, but it may be far more than a fairy tale.

Mother Holle (or Frau Holle) is one of the stories collected by the Brothers Grimm, but it may be far more than a fairy tale.

In most of the other Brothers Grimm stories, anonymous and magical beings enter the world of the protagonist to assign heroic quests, bestow blessings, or mete out punishment.

Mother Holle is quite different, in that the magical being is named, she lives in the heavens, and the protagonist of the story must go to her by paradoxically diving into a spring. When Mother Holle shakes her featherbed, the loosed feathers fall to the earth as snow. These features suggest that the story is an origin myth for a supreme Mother Goddess with roots in the early Bronze Age.

Holle seems to be a northern version of the southern Perchta or Berchta, a goddess of spinning and weaving. She had both a light and a dark aspect, the one beautiful and shining, the other old and haggard. The name Perchta seems to derive from both beraht (Bright One) and pergan (Hidden One).

In my novel Fate’s Door, I imagine Holle as a Great Mother Goddess and the first weaver to sit at the loom of fate, weaving the lives of her children – mortal and immortal – into being.

After millennia of weaving alone, she longs for company. When a wandering oread – a nymph of the mountains – climbs too high and is carried away by a cloud to Mother Holle’s cottage, she begs shelter. Mother Holle gives it, and the nymph stays for some time, recovering from her ordeal in the sky.

After millennia of weaving alone, she longs for company. When a wandering oread – a nymph of the mountains – climbs too high and is carried away by a cloud to Mother Holle’s cottage, she begs shelter. Mother Holle gives it, and the nymph stays for some time, recovering from her ordeal in the sky.

As she regains her health, the nymph helps the goddess with her tasks – both those of the household and those involved with her weaving. The two become friends. The nymph asks if she might make the cottage her home at the same moment when Mother Holle asks the nymph to stay forever, thus becoming a spirit or a numen of time.

This is the young Orroch, who eventually becomes the eldest norn.

In time, Mother Holle acquires another helper. When she is weary, the two young numeni play music to soother her and themselves, for the burden of crafting destiny is heavy.

After yet more millennia, another young nature spirit joins the family, and Orroch persuades Mother Holle to seek her freedom and leave the weaving to her helpers. Orroch promises the goddess that they will faithfully hand down the traditions of destiny to the new heirs that arise, and only then does the goddess depart.

Orroch imagines the goddess roaming the cosmos beyond even the confines of the sky, meeting strange denizens, and pursuing adventure, but no one really knows where Mother Holle has gone.

Orroch herself takes the role of weaver, while her helpers become the Pattern-maker and the Shuttle-catcher. They also seek the materials needed for the loom.

Orroch herself takes the role of weaver, while her helpers become the Pattern-maker and the Shuttle-catcher. They also seek the materials needed for the loom.

As the centuries roll by, Orroch remains steadfastly at her weaving, but newcomers take the roles of her assistants. No longer are they selected by chance. Invitations are sent to promising candidates. Orroch is content that this should be so until a certain lake nymph named Cinnisuent learns the ways of the norns. Only then does tragedy enter Orroch’s breast.

A widow had two daughters. Her stepdaughter was beautiful and industrious, but the widow favored her birth daughter, allowing the girl to become lazy and spoiled. Thus the stepdaughter had all the work to do, becoming the Cinderella of the house.

Every day the poor girl sat by a well, next to the highway, and spun so much that her fingers bled. Now it happened that one day the spindle was completely bloody, so she dipped it in the well, to wash it off. It slipped from her hand and fell in. She ran to her stepmother weeping, and told her of the mishap. She was scolded sharply and mercilessly.

Her stepmother said, “Since you have let the spindle fall in, you must fetch it out again.”

The girl went back to the well, and did not know what to do. Terrified of more scolding, she jumped into the well to fetch the spindle. As she sank below the water, she lost her senses.

When she awoke and came to herself again, she stood in a beautiful meadow where the sun was shining, and there were many thousands of flowers. She cupped one in her hand to study it more closely.

When she awoke and came to herself again, she stood in a beautiful meadow where the sun was shining, and there were many thousands of flowers. She cupped one in her hand to study it more closely.

Then she walked across the meadow and came to an oven full of bread. The bread called out, “Oh, take me out. Take me out, or I’ll burn. I’ve been thoroughly baked for a long time.” So she stepped up to it, and with a baker’s peel took everything out, one loaf after the other and set them in a wide basket lying nearby.

After that she walked further and came to a tree laden with apples. “Shake me. Shake me. My apples are all ripe,” cried the tree. She shook the tree until the apples fell as though it were raining fruit. When none were left in the tree, she gathered them into a deep basket which lay under the tree, and then continued on her way.

Finally she came to a small cottage. An old woman peered out through the open window. She had very large teeth, which frightened the girl, who wanted to run away. But the old woman called out to her, “Don’t be afraid, dear child. Stay here with me, and if you keep my household in an orderly fashion, all will go well with you. Only you must take care to make my bed well and shake it diligently until the feathers fly, then it will snow in the world. I am Mother Holle.”

Because the old woman spoke so kindly to her, the girl took heart, agreed, and started in her service. The girl took care of everything to Mother Holle’s satisfaction and always shook her featherbed vigorously until the feathers flew about like snowflakes. Therefore she had a good life with her: no angry words, and roast meat to eat every day.

Because the old woman spoke so kindly to her, the girl took heart, agreed, and started in her service. The girl took care of everything to Mother Holle’s satisfaction and always shook her featherbed vigorously until the feathers flew about like snowflakes. Therefore she had a good life with her: no angry words, and roast meat to eat every day.

After she had been with Mother Holle for a time, she became sad. At first she did not know what was the matter with her, but at last she determined that it was homesickness. Even though she was many thousands of times better off with Mother Holle than at home, still she had a yearning to return. Finally she said to the old woman, “I have such a longing for home, and even though I am very well off here, I cannot stay longer. I must go up again to my own people.”

Mother Holle said, “I am pleased that you long for your home again, and because you have served me so faithfully, I will take you back myself.” With that she took her by the hand and led her to a large gate.

The gate was opened, and while the girl was standing under it, an immense rain of gold fell, and all the gold stuck to her, so that she was completely covered with it. “This is yours because you have been so industrious,” said Mother Holle, and at the same time she gave her back the spindle which had fallen into the well.

Then the gate was closed and the girl found herself on earth again, not far from her mother’s house. As she entered the yard the rooster, sitting on the well, cried, “Cock-a-doodle-doo, our golden girl is here anew.”

The girl went inside and, as she arrived all covered with gold, she was well received, both by her mother and her sister. The girl told all that had happened to her, and when the mother heard how she had come to the great wealth, she wanted to achieve the same fortune for her other daughter. She made the lazy girl go and sit by the well and spin. To make her spindle bloody, the girl shoved her hand into a thorn bush and pricked her fingers. Then she threw the spindle into the well, and jumped in after it.

Like the other girl, she too came to the beautiful meadow and walked along the same path. When she came to the oven, the bread cried again, “Oh, take me out. Take me out, or else I’ll burn. I’ve been thoroughly baked for a long time.”

But the lazy girl answered, “As if I would want to get all dirty,” and walked away.

Next she came to the apple tree. It cried out, “Oh, shake me. Shake me. My apples are all ripe.”

But the girl answered, “Oh yes, one could fall on my head,” and with that she walked on.

When she came to Mother Holle’s house, she was not afraid, because she had already heard about her large teeth, and she immediately began to work for her. On the first day she forced herself, was industrious, and obeyed Mother Holle, because she was thinking about all the gold that she would receive.

But on the second day she grew lazy, on the third day even more so, and then she didn’t even want to get up in the morning.

She did not make the bed for Mother Holle, the way she was supposed to, and she did not shake it until the feathers flew. Mother Holle soon became tired of this and dismissed her from her duties. This was just what the lazy girl wanted. She thought that she would now get the rain of gold.

Mother Holle led her to the gate. She stood beneath it, but instead of gold, a large kettle full of pitch spilled over her. “That is the reward for your services,” said Mother Holle, and closed the gate. The lazy girl walked home, entirely covered with pitch.

As soon as the rooster on the well saw her, he cried out, “Cock-a-doodle-doo, our dirty girl is here anew.”

The pitch stuck fast to her, and did not come off as long as she lived.

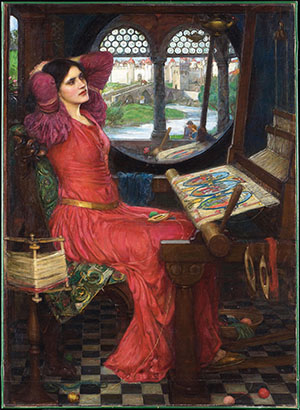

When I envision Mother Holle as she appears in my protagonist’s thoughts, I see a queenly woman resembling those painted by the Pre-Raphaelites of the 19th century.

Therefore, when I began my search for images for this post, I looked among the works of the Pre-Raphaelites. Although John William Waterhouse painted several decades after the break-up of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, his style blended theirs with that of his contemporaries, the Impressionists.

And it was amongst the Waterhouse paintings that I found images that matched those of my mind’s eye, as you can see from the selections above. While searching, I also discovered a video combining a slide show of many Waterhouse paintings with the music “Tu chiami una vita” by Jan A.P. Kaczmarek, lyrics by Salvatore Quasimodo. It is so beautiful that I simply must share it with you. 😀

For more about the world of Fate’s Door, see:

Nerine’s Room

Brocade and Drawlooms

Cottage of the Norns

The Norns of Fate’s Door

The Baltic Sea

The Ancient Goths

Lugh and the Lunasad

Crossing the Danube

The Keltoi of Európi

For more about Mother Holle, see:

Mother Hulda on Wikipedia

Frau Holle on Wikipedia

Perchta on Wikipedia

For more about John William Waterhouse, see:

John William Waterhouse on Wikipedia

Waterhouse Signatures on the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood

The Winds of Waterhouse on the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood

Waterhouse’s Undine and Mermaids on the Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood