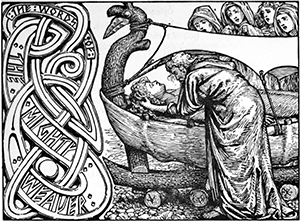

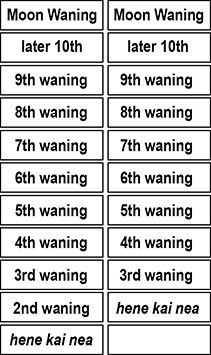

The three Fates appeared in many of the mythologies of ancient Europe. They were often envisioned as goddesses weaving on a loom, the tapestry thus created shaping the destinies of both mortals and gods.

The ancient Greeks had the three Moirai. The word moira meant portion or share or lot of booty or treasure, and over time came to refer to one’s portion or lot in life, one’s fate.

The ancient Greeks had the three Moirai. The word moira meant portion or share or lot of booty or treasure, and over time came to refer to one’s portion or lot in life, one’s fate.

Clotho, the spinner, spun the thread of life, the animating energy that gifted mortal and immortal with awareness and existence. She was also said to be a singer, singing of the things that are, the present.

Lachesis was the allotter or the drawer of lots, and she measured the thread of life meted out to each individual with her measuring rod. The beginning mark signified birth, while the ending mark was death. When she joined her sisters in song, she sang of the things that were, the past.

Atropos was “the unturning one,” also called inexorable or inevitable. She chose the nature of each person’s death, and when that dread moment arrived, cut the thread of life with her knife. She sang of the things that would be, the future.

The ancient Romans had their own version of the Fates: the Parcae, the goddesses of destiny.

Nona, named after the ninth month of pregnancy, spun the thread of life. Decima, also revered as the goddess of childbirth, measured the thread of life with her rod. And Morta, the “Dead One,” chose the manner of each indiviual’s death and cut the thread of life.

Nona, named after the ninth month of pregnancy, spun the thread of life. Decima, also revered as the goddess of childbirth, measured the thread of life with her rod. And Morta, the “Dead One,” chose the manner of each indiviual’s death and cut the thread of life.

It’s worth noting the slightly different connotations connected to “destiny” versus “fate.” Fate implies that the events of an individual’s life are ordered, inevitable, and unavoidable. While destiny refers to the finality of events as they have worked themselves out through the passage of time.

I can’t help wondering if the Romans conceived of a little “wiggle room” being available to the individual in the form of choice, where the Greeks may have believed that their lives were entirely predestined. I don’t have the answer to that question, but the Fates I portray in Fate’s Door adhere more to the Roman ideal of destiny than the Greek one of fate.

Given that my story – Fate’s Door – is set in the 4th century BC, when the Hellene culture was ascendant, why didn’t I use the Greek personifications of the Fates? Why did I chose the Norse Norns instead?

Given that my story – Fate’s Door – is set in the 4th century BC, when the Hellene culture was ascendant, why didn’t I use the Greek personifications of the Fates? Why did I chose the Norse Norns instead?

Perhaps the most honest answer is simply that the Greek Morai felt wrong for the roles in Fate’s Door, but there were a few more elements that had bearing on my creative vision.

For one, the Greek Morai are often portrayed as living in some desolate region far from the bounds of civilization. A wilderness at the foot of craggy mountains on the edge of the world. Or a dry and desert region below a looming cliff of black rock. They certainly lived nowhere near Mount Olympus.

If my Fates dwelt in the far north, as I envisioned them, then wouldn’t the mythologies of the Nordic peoples influence their manifestation?

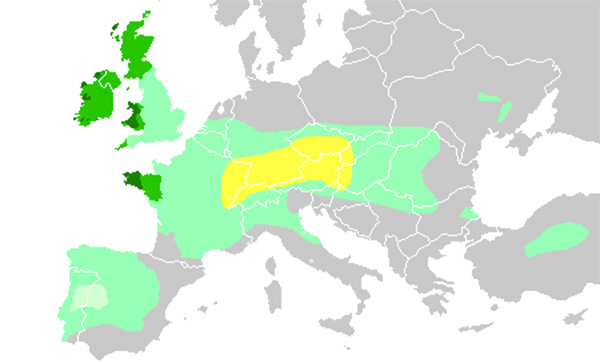

The Hellenes might envision them as the Morai and speak of them as Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. But just as the Keltoi developed a different vision for Hermes and called him Lugh, so the northern Scandians would have their own idea of the Fates. The Norns might easily conform more closely to the Scandian ideal, even while the Greeks pursued their own vision.

My other reason for choosing the Norse Norns is more subtle, having to do with the cosmology of my story, and how I mapped the mythologies of the ancient world onto the history of that world.

I imagine the greater deities such as Zeus and Athena as arising from the cultural consciousness of the times. They possess more definition and permanence than the lesser demi-gods and nature spirits representing specific localities, such as the the Hippocrene Springs, or cultural concepts such as loyalty and honor.

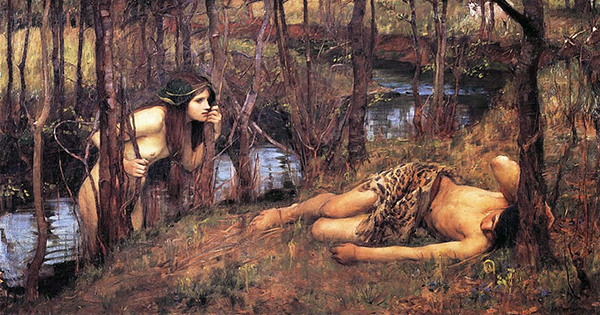

Thus, while Zeus is always Zeus, the naiad of the Hippocrene Springs merely holds that role for a limited time, and passes on to another station or post when she is ready for a change.

Sea spirits (nereides), tree spirits (dryads), mountain spirits (oreads) and more animated the cosmos of the ancients.

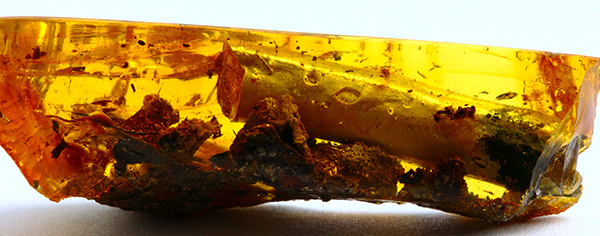

My Fates are time spirits, going back to the earliest of eras when sewing needles were invented in 19,000 BC in pre-historic France, or even earlier when thread was created from flax in 36,000 BC in Russia-to-be.

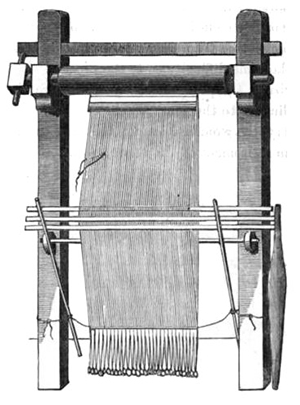

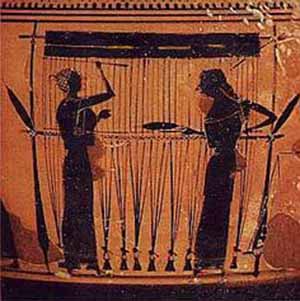

The very first weaver of destiny was a goddess, Mother Holle, working at a primitive ground loom. But as humanity acquired greater sophistication, and their world view grew more complex, Mother Holle acquired helpers – spirits of time, the Norns – and eventually abdicated her role to her helpers entirely.

As humans developed better weaving tools, the Norns benefited as well. Although the task of transferring the tapestry of the world from a ground loom to a vertical loom must have been formidable indeed.

Because my Norns are spirits of time, they have some access to both the past and the future. Some of their materials, such as pivoting scissors instead of spring scissors, come from the future, as does the complex brocade loom that they are using when Nerine arrives.

Because my Norns are spirits of time, they have some access to both the past and the future. Some of their materials, such as pivoting scissors instead of spring scissors, come from the future, as does the complex brocade loom that they are using when Nerine arrives.

Of course, my Norns don’t conform exactly to the Norse Urthr (“fate”), Verthandi (“in the making”), and Skuld (“debt” or “future”).

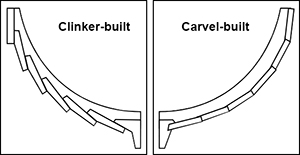

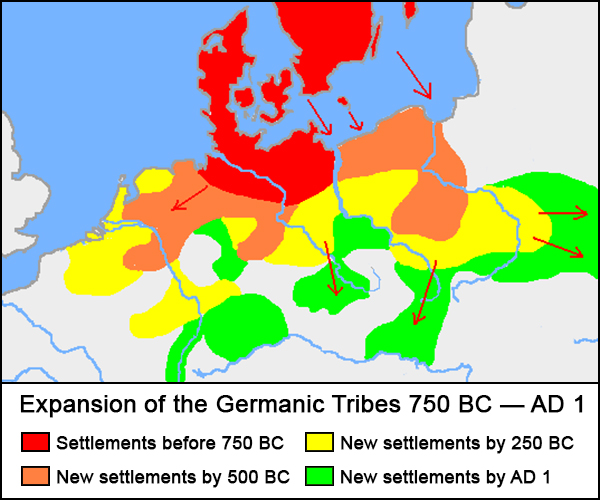

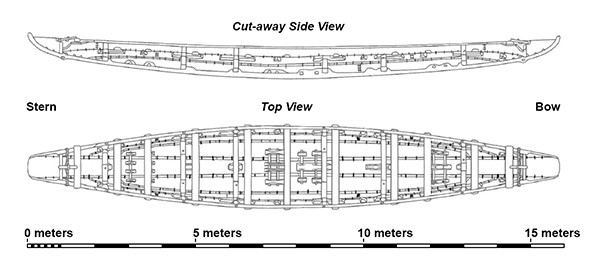

Instead, I have Tynghed (derived from the Welsh “destiny”), Eowys (Anglo-Saxon “horse-wise”), and Orroch (Early English “oar”). I suspect that Urthr, Verthandi, and Skuld might have served the great loom of fate sometime after my story takes place, in the centuries when the Roman Empire dominated and the Germanic tribes – with their Norse dieties – nibbled at the Roman borders.

But like their later counterparts, my Tynghed, Eowys, and Orroch draw water from the Well of Fate, with which to water the World Tree, and they watch the visions of destiny in the Well’s dark magic.

For more about the world of Fate’s Door, see:

The Baltic Sea

The Ancient Goths

Lugh and the Lunasad

Crossing the Danube

The Keltoi of Európi

Vertical Looms

Names in Ancient Greece

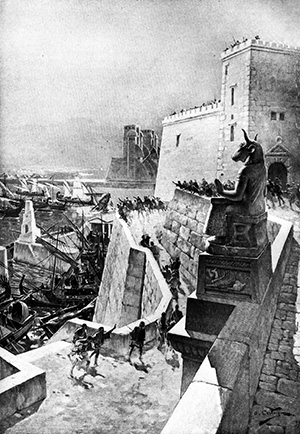

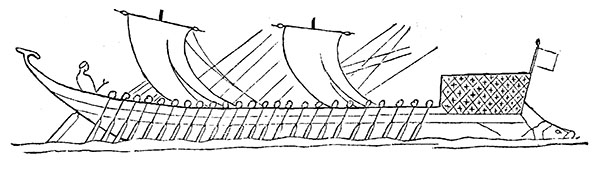

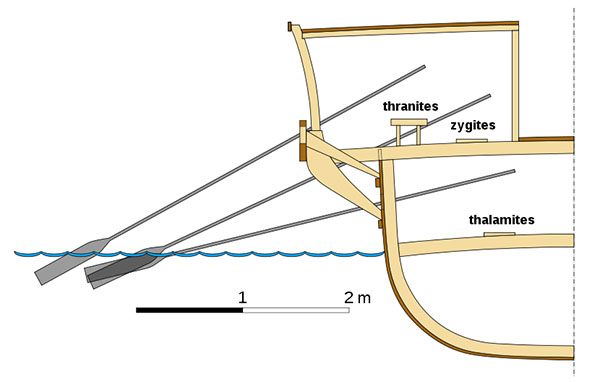

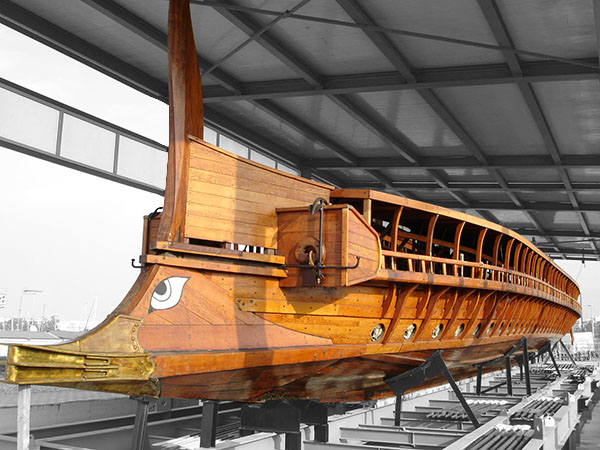

Warships of the Ancient Mediterranean

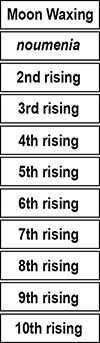

Calendar of the Ancient Mediterranean

For more about the three Fates, see:

The Moirai

The Parcae

The Norns