When I started writing Fate’s Door – a book in which the three fates who weave the destiny of the world play important roles – I expected that I would need to learn a lot about weaving. What I didn’t expect was that weaving would enter the story before my heroine got anywhere near the cottage of the fates.

When I started writing Fate’s Door – a book in which the three fates who weave the destiny of the world play important roles – I expected that I would need to learn a lot about weaving. What I didn’t expect was that weaving would enter the story before my heroine got anywhere near the cottage of the fates.

But so it was.

Nerine is a young sea nymph. She makes friends with a boy who lives on land: Altairos. And Altairos naturally introduces her to his nurse, Calla. Calla begins teaching Nerine to weave. And there I was, needing to know more about the textile arts. 😀

The culture of the Mediterranean in the Hellenistic era used vertical looms, and I’ll be writing a blog post about them soon. But Calla prefers the more ancient style of loom: the ground loom.

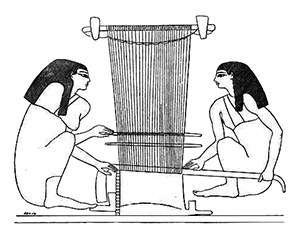

There is archaeological evidence that Neolithic peoples as far back as 6000 BC used ground looms, but the ancient Egyptians used them as well, from 5000 BC until sometime after 1550 BC, when the vertical loom was developed.

There is archaeological evidence that Neolithic peoples as far back as 6000 BC used ground looms, but the ancient Egyptians used them as well, from 5000 BC until sometime after 1550 BC, when the vertical loom was developed.

Calla could have requested either type of loom for herself. She is greatly honored and loved by the royal family of Zakynthos, and they would have provided whatever she wanted. But the vertical loom requires greater strength from the weaver, as well as a lot of standing, and Calla is old. She wants to weave while sitting.

Calla’s loom is a much finer version of the ground loom than the original instrument used in 6000 BC.

The very first ground looms were simply four sticks plunged into the soil, one pair placed roughly 3 feet apart in front of the weaver and another pair – also 3 feet apart – placed 6 to 10 feet away from the weaver.

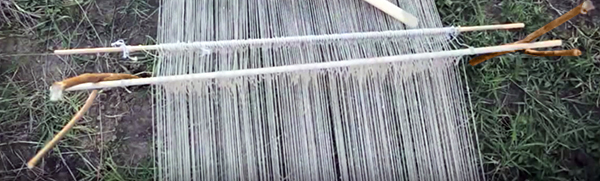

Narrow beams at each end were secured to the sticks, and the warp threads were tied to the beams. Two sticks (lease rods) were used to lift the long warp threads on these early looms, allowing the short weft threads to be passed across the warp.

Later on, the heddle was invented, providing a more convenient way to separate the warp strands.

As looms became more sophisticated, so did heddle design. But the heddles for a ground loom were essentially two rods with loops of string attaching every other warp thread to one and the alternate every other warp thread to the other.

The weaver would lift one heddle into the heddle jacks – two Y-shaped sticks, one on either side of the warp threads – and pass the shuttle through. After beating the weft thread firmly against the previous weft thread, she would lift the first heddle down, lift the other heddle into the jacks, and pass the shuttle across again.

Nomadic people still use these simple ground looms, because they are so portable. You just pull the sticks out of the ground and pack the whole kit and caboodle up.

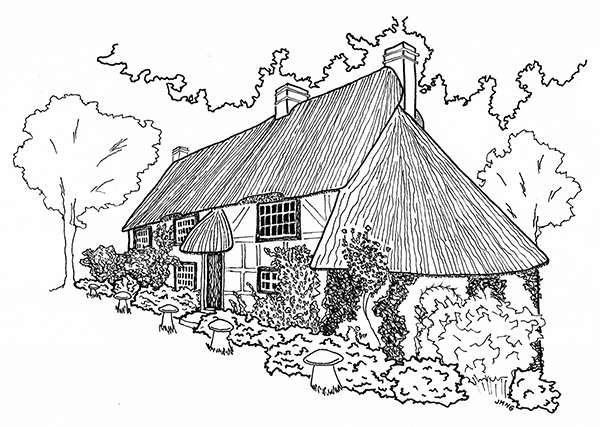

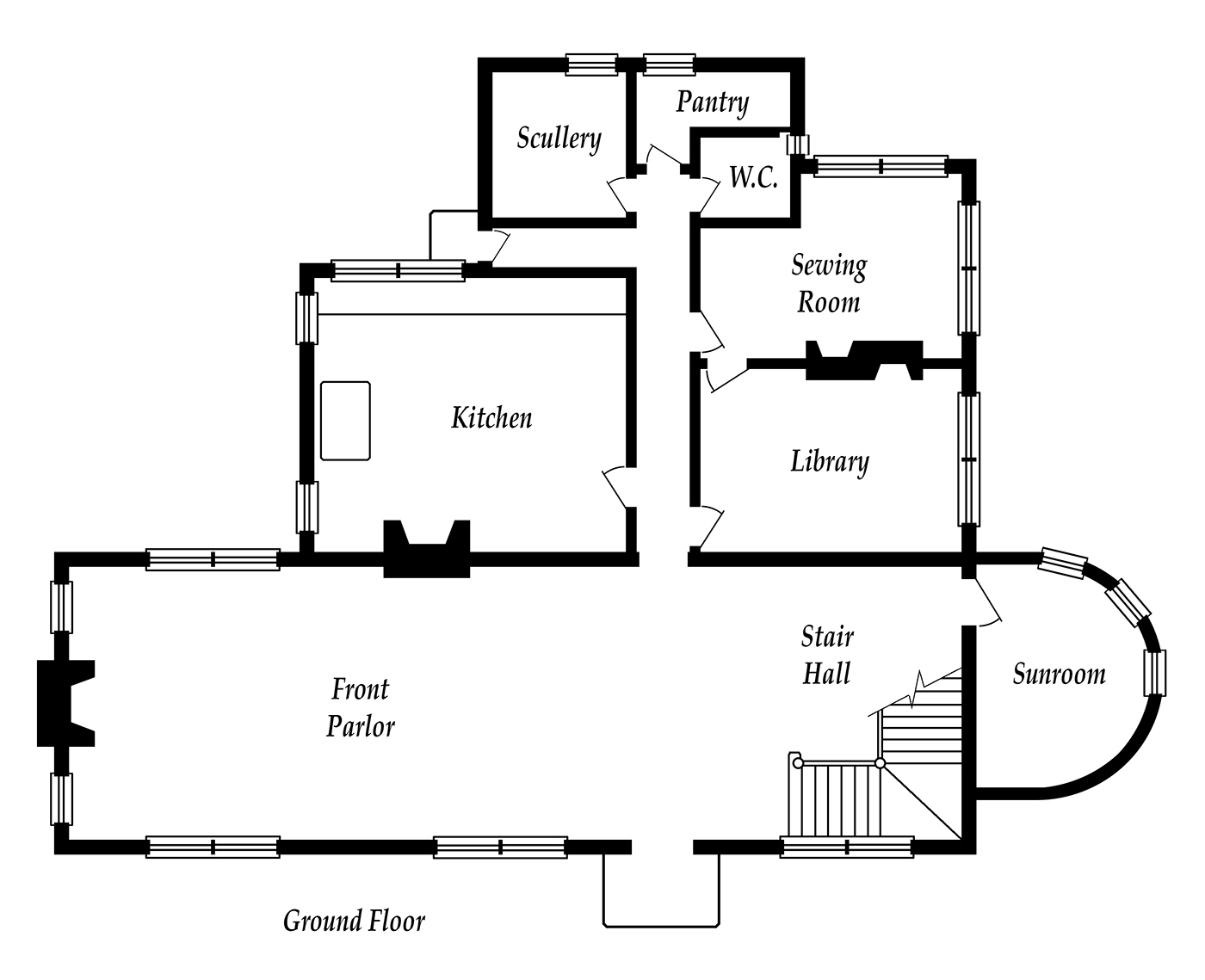

But Calla weaves in the comfort of her own home, and her loom is created by finely smoothed wooden cylinders set into a raised platform faced by tiles. Brackets along the sides of the platform allow her to move the heddle jacks as the fabric progresses. As the working edge of the fabric moves away from her, she can either sit at the side of the loom to continue weaving, or place a cushion below the fabric and sit directly on it.

The fabric in the video below is a very coarse one, woven loosely of coarse thread. But it is possible to weave very fine cloth on such a loom. The ancient Egyptians used flax threads so fine and smooth, and wove it so skillfully, that the resulting linen was fit for royalty. Indeed, it was in great demand for export to Arabia and India due to its high quality.

For more about the world of Fate’s Door, see:

Merchant Ships of the Ancient Mediterranean

Garb of the Sea People

Measurement in Ancient Greece

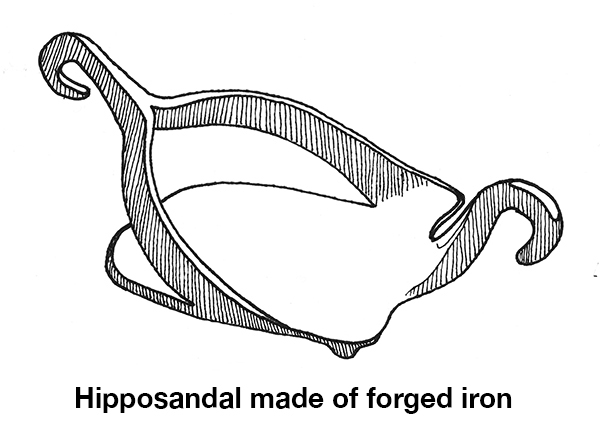

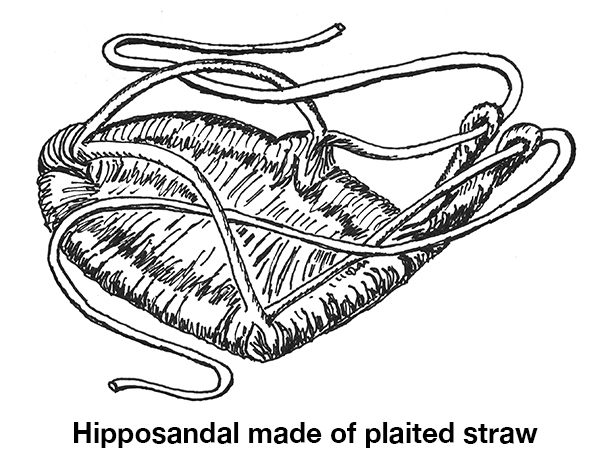

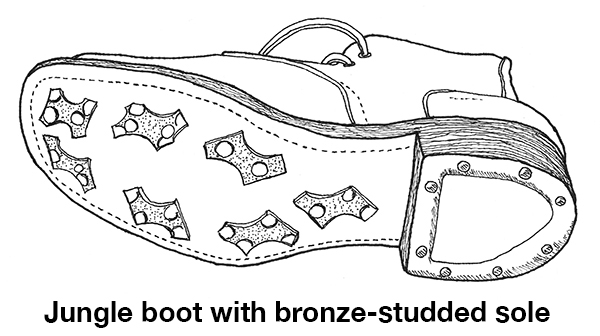

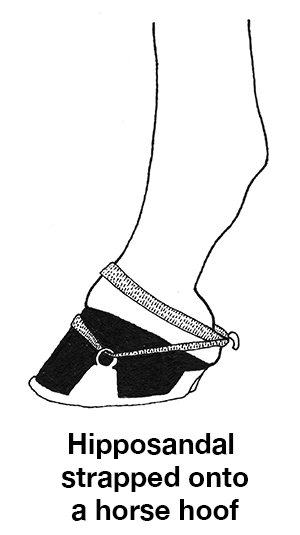

Horse Sandals and the 4th Century BC

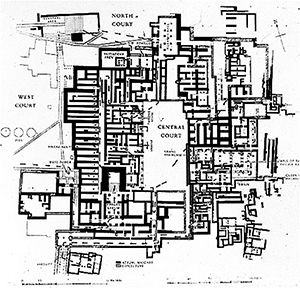

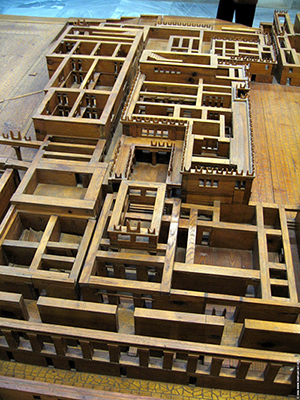

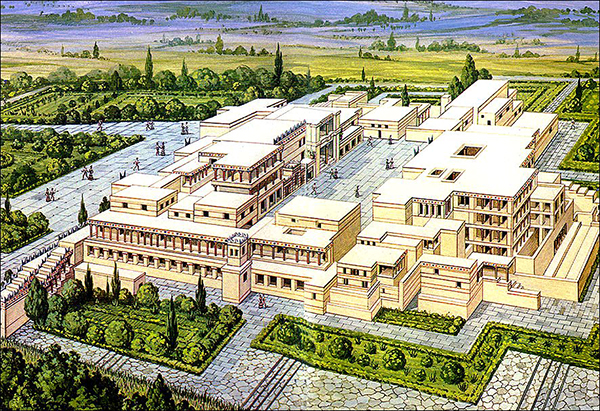

Knossos, Model for Altairos’ Home

For more about ground looms and weaving on them, see:

Nomadic Looms

Flax and Linen in Pharaonic Egypt

Ancient Egyptian Linen

Types of Looms