Back in March, I mentioned that I’d been doing some new things on the cooking and nutrition front. I imagined telling you all about it when I finished my revisions on The Tally Master and published the novel.

Well…the digital edition of The Tally Master released April 26, and the paperback roughly a month later in May. In fact, I’m now well started on my next book, with over 10,000 words and counting in the manuscript.

I must plead guilty to dragging my heels on blogging about food.

Why?

Because the biology of nutrition is amazingly complex and, at this point, I’ve read so much about it that when I discover new-to-me information, I’m connecting that information to large matrix of facts forming a landscape detailed and variegated enough that it’s challenging to communicate about it clearly and succinctly.

The overall picture has come into better and better focus for me. I really understand what I’m seeing, and it’s very consistent. But conveying what I see is harder than when I saw less, and the picture seemed simpler.

Yet it’s important stuff. Nutrition is one of the foundational elements determining whether a person merely survives…or thrives. So I’m going to make an effort to share the latest things I’ve been learning.

Today I want to talk about insulin.

Insulin is a hormone.

Hormones are the biochemical messengers of the body. Typically they are secreted by one set of cells, then transported in the bloodstream (or, sometimes, the lymphatic system) to another part of the body, where they bond to specific receptors there.

In the case of insulin, it is secreted by the beta cells of the pancreas, moves through the bloodstream, and affects nearly every cell in the body. Insulin is a master hormone. (Many other hormones possess a narrower window of effect.)

Insulin controls:

• energy storage

• cell growth

• cell repair

• reproduction

• and blood sugar levels

It is the last item on that list – blood sugar levels, technically blood glucose levels – that I’m going to focus on.

Let’s see how it works.

When you eat a carbohydrate – bread, pasta, cookies – your digestion breaks the large molecules down into glucose, which transfers through the lining of your small intestine into your bloodstream.

Your blood sugar rises.

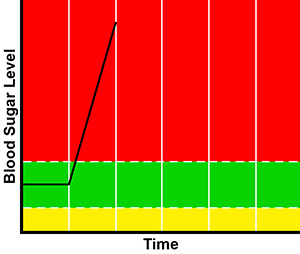

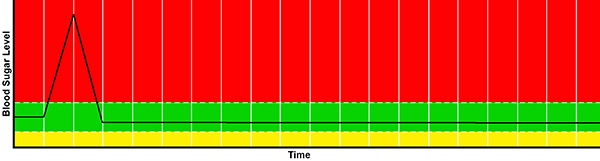

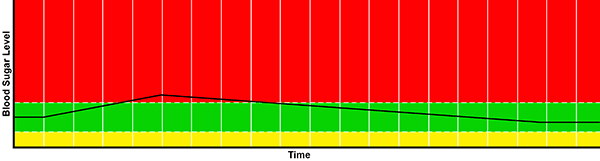

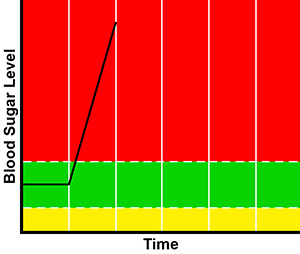

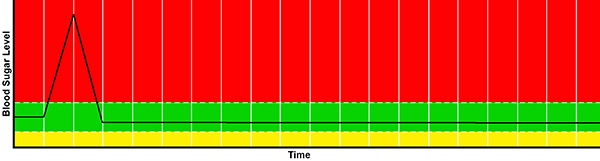

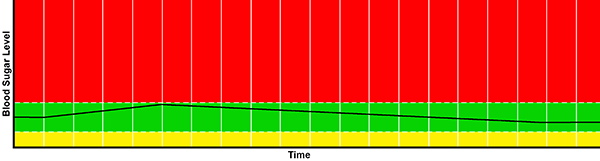

If you ate the cookies – or the cake – which has lots of sucrose and which doesn’t require much digesting to be broken into its component parts of fructose and glucose, your blood sugar spikes. Something like this:

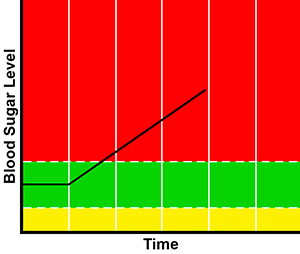

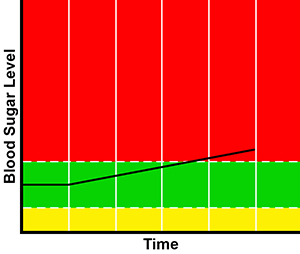

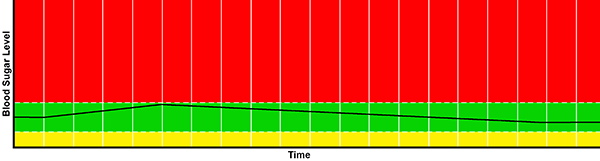

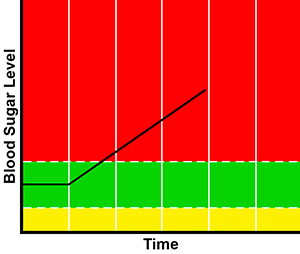

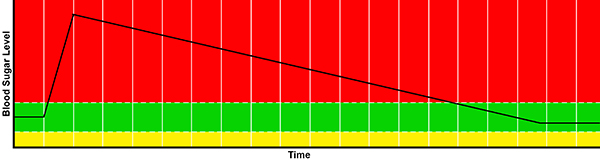

If you ate whole grain rye bread instead, your blood sugar rises more gradually, because all the fiber in the rye bread slows down the rate at which the carbohydrate molecules are broken down into glucose. But – and this is key – your blood sugar does rise. Something like this:

Your body is designed to operate within a very narrow range regarding blood sugar level.

Too little, and some critical operations that depend on glucose for their energy source won’t get enough of it.

This would be very bad.

But there are two important things to keep in mind regarding the potential scenario of low blood sugar.

1 • Foods are rarely pure concentrations of the three macro-nutrients: protein, fat, and carbohydrate.

All foods are made of a combination of these macro-nutrients, each in varying ratios. Butter is mostly fat, but every tablespoon has approximately .1 gram of protein and .01 gram of carbohydrate in it.

Meats are almost entirely protein and fat, but a 6-ounce serving of liver has 8 grams of carbohydrates. Not much, but some. Of course, vegetables and fruits are composed mostly of carbohydrates, all contained in a hefty fiber matrix along with huge packets of vitamins and minerals. But there’s no need to eat bread and pasta to prevent low blood sugar. You’ll get plenty of glucose without them!

2 • Your body can and will make glucose from certain amino acids.

This is why there is no minimum dietary requirement for carbohydrates, unlike – for example – the dietary requirement for protein or that for the essential fatty acids, linoleic and alpha-linolenic.

(Your body can make many, even most, of the amino acids that are the building blocks of protein. But it cannot make them all. There are 9 amino acids that you must get from food. The same is true for the fatty acids: most can be synthesized by your body, but not the two I named above, which must also be obtained from food.)

While I’m on the subject of what the human body can synthesize versus what it must receive from food, I want to touch on an obscure limitation possessed by people with Scandinavian, Innuit, Northern European, or sea coast ancestry. It has personal interest to me, since I’m half Swedish, and the other half comes from Scotland and England.

People with these northern roots often lack the enzymes that convert alpha-linolenic acid into EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA (docosahexaenoic acid), two omega-3 fatty acids required for the proper functioning of the immune and nervous systems. The reason behind this lack is that their ancestors ate large amounts of cold-water fish, which supplied all the requisite EPA and DHA. Over time and across generations, the bodies of the northerners simply ceased to manufacture the enzymes that do the conversion.

EPA is found only in animal foods. DHA is present in some algae, but in very low amounts, too low to supply enough.

This explains to me why I became more and more chronically fatigued, and caught colds the instant I was exposed them, when I was in my early thirties and following a vegetarian diet. I was eating whole grains and legumes with a vengeance, but my health got worse and worse, until I added meat back into my repertoire.

However, to get back to my topic here: carbohydrates are not like the nine essential amino acids or the two essential fatty acids. Or even like EPA and DHA for northerners. Your body can make glucose, when it needs it. You don’t need to eat it.

Let’s now consider high blood sugar.

High blood sugar levels are nearly as bad for you as low.

High blood sugar acts essentially as a wrecking crew in your body, damaging your liver, your pancreas, your kidneys, your blood vessels, your brain, and your peripheral nerves. Just like a wrecking ball taking down a rickety tenement.

It’s critically important that your blood sugar level stay in the Goldilocks zone: not too low, not too high, but just right.

(Yes, I know that the Goldilocks zone typically refers to a donut of space around a star in which planets can possess water that is liquid. But the term fits here, too.)

I presented a graph representing your blood sugar level after eating dessert. And I presented another representing your blood sugar level after eating some “healthy” whole grain bread. (For the record, white bread made from refined flour spikes your blood sugar just like cake. Beware those crusty loaves of delicious French bread. Just sayin’.)

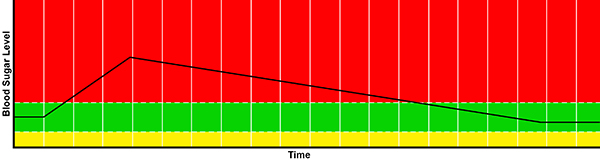

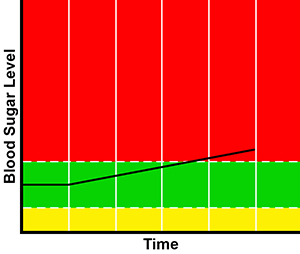

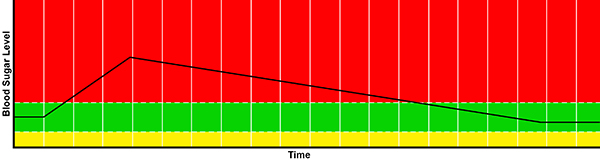

Let’s consider another scenario: your blood sugar after eating baked carrots drizzled with clarified butter or, perhaps, roasted eggplant drizzled with olive oil and sprinkled with some sea salt and freshly grated black pepper. That would look something like this:

Now let’s think about these three eating scenarios.

The first – eating a sugar-laden dessert – yields a sky high level of blood glucose, much like the big kapow of a wrecking ball slamming into a brick building, indeed. Lots of damage. Which your body then repairs. Usually qute well when you are young. Less well, and more slowly, when you are in your forties or older.

The second scenario – eating whole grain bread – also yields blood sugar levels that are quite high, but not quite as high as eating cakes, candy, or soda sweetened with high-fructose con syrup. It’s more like the men in a wrecking crew who are busily dissassembling the framing in a house: unbolting the beams that support the floor, pulling nails in the 2x4s of the thewalls, working hard to take the thing apart.

Again, your body repairs the damage. Almost without a hitch, if you are young. Less easily, when you are older.

In the third scenario – eating a vegetable – your blood sugar barely rises out of the “just right” Goldilocks zone at all. The damage done is minimal, the equivalent of a hinge loosened on a door or a roof tile blown off in the wind. Your body repairs the damage, and need not use much in the way of resources to do so. Your body can support this kind of repair for a long, long time.

So far, I’ve been talking more about blood sugar (which insulin is designed to regulate) than I have about insulin itself.

So let’s move on to insulin.

When you eat a food that causes your blood sugar to rise, those beta cells in your pancreas secrete insulin into your bloodstream. The insulin signals the cells in your body to pull the glucose out of your bloodstream and pack it away into storage.

Where is this storage?

The first storage spots are located in the liver and in the muscles. In both, the glucose is converted into a complex carbohydrate called glycogen.

Glycogen in the liver can easily be converted back into glucose and released back intot the bloodstream to correct low blood sugar when needed.

Glycogen in your muscles stays there to be used by your muscles when they do work. This muscular glygogen cannot be released back into your bloodstream. It stays in storage until your muscles use it up.

But, here’s the thing: your body has limited room for storing glycogen. Between your liver and your muscles, you store enough to allow you to work out hard for about 90 minutes.

What happens if you don’t work out? What if you mostly sit at your desk? And just putter around your house at the end of the day?

Well, some of the glycogen in your liver is probably used up to keep your blood sugar stable between meals. But the glycogen in your muscles simply stays there. Which means that when you eat your next piece of rye toast – or that leftover slice of birthday cake – most of your storage space is already full.

So where does the glucose go, when there’s no room at the inn?

It must not stay in the bloodstream. That would kill you fairly quickly. The muscles are full – they won’t take any more. The liver might have room for a little bit. But what happens to the rest?

Your liver converts the extra glucose into a saturated fat called palmitic acid. Some of the palmitic acid is then bundled together in groups of three to form triglycerides.

The triglycerides and fatty acids are then released into your bloodstream to be taken up by your fat cells. Your fat cells also have a limit to their storage capacity, but they are capable of taking in more than they are designed to hold. Your body doesn’t make more fat cells when you’ve got excess fatty acids and triglycerides to store. (The number of your fat cells is set during childhood and adolescence.) It just packs more into each of the existing fat cells.

Each fat cell stretches to accommodate the overpacking, and it becomes inflamed.

Eventually, the overpacked fat cell simply cannot take anymore. Bloated and inflamed, it puts up a “no vacancy” sign, and the excess triglycerides and fatty acids circulate in your bloodstream. Not good! (High levels of triglycerides in the blood are a known marker for cardiovascular disease.)

I’m going to return to my three scenarios – eating dessert, eating bread, eating vegetables – in a moment, putting insulin in the picture. But before I do that, let me say a few words about inflammation.

Inflammation in our bodies is regulated by the immune system. It is part of the repair cycle that follows an acute injury (a broken bone, a bruising blow, a burn or a cut) or an infection (by bacteria, a virus, or a parasite).

The immune system ramps up to fight and then to repair the damage. When the repair work is complete, the inflammation passes, and the immune system stands down. It’s ready, sure, for the next time. But in between fights, it’s idling. And while it’s idling, it’s doing low-level routine maintenance.

To use analogy: it’s tightening up that loose hinge, driving in an extra nail to that squeaking floorboard, stocking the freezer with chicken soup, painting the shutters and cleaning the windows, washing the dishes.

When your immune system is ramped up and fighting a fire – healing an acute injury or repelling an invader – it does not perform routine maintenance. These small jobs go undone until the next lull.

Chronic inflammation – which is part and parcel of overstretched fat cells – means your immune system is diverting some of its resources to fight a fire. Resources which are needed for routine maintenance. Necessary chores are being left undone as your immune system sends help to the inflamed fat cells.

Chronic inflammation – inflammaton that persists and has no end – is never a good thing. And when we are overweight, we are dealing with chronic inflammation. The more avoirdupois, the higher the level of inflammation.

One more note on inflammation: insulin itself is inflammatory. The longer it hangs out in your bloodstream to clean up glucose, the more it contributes to inflammation.

Okay, now let’s get back my three eating scenarios.

What happens with insulin after you eat cake?

The answer to this question is highly influenced by how insulin resistent your cells are. Typically, when you are young and haven’t been consuming sugar and grains for decades, your cells are not resistant. Which means your pancreas secretes a moderate amount of insulin, your liver and muscles take up glucose in the form of glycogen, and your blood sugar level returns to normal. That would look somoething like this:

That’s a pretty good scenario. Blood sugar isn’t elevated for long, which means the damage done is limited. Insulin didn’t stay in your bloodstream for long, so it didn’t contribute much toward creating inflammation. Your liver and muscles had room for all the glycogen. And then, because were a kid, you went outside and played tag with your friends, emptying much of the glycogen from your muscles and making room for more. Plus, since there was no insulin in your blood, some of the fat in your fat cells was emptied out and converted for energy as well, making room for storage there and ensuring that the cell didn’t become overpacked.

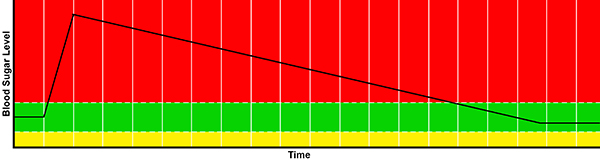

But when you’re 45…or 55…or 65, it doesn’t look like that.

It’s more like this:

Your cells are insulin-resistent from decades of eating sugar and grains, which means it takes more insulin and more time to pack away all that glucose. Your blood sugar is elevated for longer, damaging your body for the entire interval. Your insulin levels are elevated for longer, contributing to inflammation for the entire time. And while your bloodstream is brimming with insulin, your body is unable to withdraw fat from fat cells. (See Test first, then conclude! for more about the one-way door that insulin creates.)

On top of that, you had a stressful day at the office, and when you arrived home you were too exhausted to go to the gym to work out. So there’s not much room in your muscles for any glycogen. Your liver converts it to fatty acids and triglycerides, which are packed away into your fat cells. And these stretched fat cells are, by definition, inflamed fat cells. Which is why the tendonitis in your shoulder (or whatever chronic problem you’re fighting) refuses to heal.

The scenario with whole grain bread or brown rice isn’t much better:

Sure, your blood sugar does not spike as high, but it is still elevated for a long time, doing damage the whole while. Your pancreas must still secrete a lot of insulin, which contributes to inflammation. And while the insulin is present, your cells are forced to run on glucose (glycogen) for energy. No fat can be withdrawn from your fat cells to be processed into ketone bodies, the preferred food of the brain.

Now let’s consider the scenario in which you eat vegetables.

Because your blood sugar barely rises above the optimum level and does not stay there for long, not much damage is done. Furthermore, it does not take much insulin to bring it back down. Which means the insulin has little opportunity to cause inflammation. And, since insulin is not present for long, your body is soon free to withdraw fat from your fat cells and use it for energy.

Withdrawing fat from the fat cells means they get smaller. As they shrink in size, their degree of inflammation reduces. Eventually, if you keep allowing your body to use fat for fuel, the inflammation goes away entirely. Your immune system devotes more and more of its resources to normal repair and maintenance. Your spare tire shrinks. Your knees stop aching.

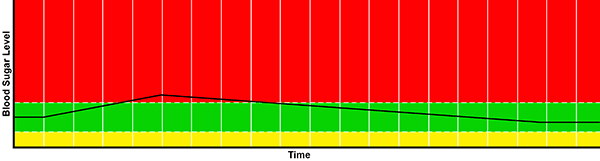

Let’s consider one more scenario.

Instead of eating just baked carrots drizzled in clarified butter, you also eat seared chicken breasts with a few olives as garnish.

The protein in the chicken and the oil in the olives (plus the fat in the clarified butter and the fiber in the carrots) will cause the carbohydrates in the carrots to be broken down and assimilated even more gradually, so that your blood sugar might never leave the Goldilocks zone at all. Check it out!

I want to visit one more tangent before I conclude: nutrient density.

What does the term mean?

The proportion of nutrients present in a food in comparison to the calories it provides. The nutrients of primary interest are vitamins, minerals, phytonutrients, and the nine essential amino acids. The more nutrient-dense a food is, the more it supports optimal functioning and health.

At one end of the scale are sugar and white flour. They provide no vitamins, no minerals, and no amino acids at all. They are truly empty calories. Sugar is merely glucose plus fructose, and both of these substances rapidly unhook from one another under digestion, the glucose yielding all the damage I’ve been discussing above.

White flour, when digested, also yields glucose, resulting in damage nearly identical to that produced by sugar, and providing no nutrients.

But whole grains are not much better.

But whole grains are not much better.

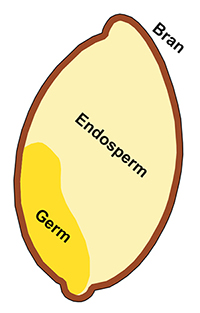

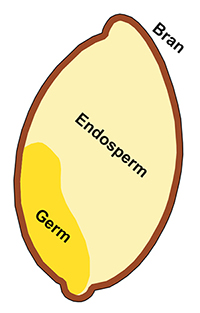

Let’s take a look at the structure of a grain kernel.

The germ and the bran are where you find vitamins, minerals, and fiber. The endosperm provides energy – calories – that allows the seedling plant to grow. (The plant’s nutrients will come from from the soil through its roots or be synthesized by the plant from sunlight, carbon dioxide, and water.)

White flour is made from the endosperm. The bran and the germ are discarded.

Whole grain flour keeps the bran and the germ, but here’s the catch: the bulk of even whole grain flour is provided by the nutrient-free endosperm, and most of the nutrients present in the bran and the germ are not bio-available. That is, they are chemically bound so tightly that digestion cannot unhook them to pass them through the lining of the small intestine and into our bodies where they can be used.

Even worse, the phytates in the bran (present to protect the seed) bind calcium and other minerals from other foods present in the digestive tract and carry these valuable substances out of the body altogether.

Grains are not nutrient-dense.

And every vitamin or mineral that is present in whole grains is present in far larger amounts and with greater bio-availability in vegetables, fruits, eggs, seafood, and meat.

Vegetables, fruits, eggs, seafood, and meat are nutrient dense.

I’ll be posting more of my latest revelations about food and nutrition over the coming weeks and months. In the meantime, if you’d like to delve deeper on your own, I can recommend two books.

It Starts with Food by Dallas and Melissa Hartwig is an excellent resource with solid information presented in a lighthearted, friendly way.

It Starts with Food by Dallas and Melissa Hartwig is an excellent resource with solid information presented in a lighthearted, friendly way.

It’s an easy introduction to some key principles, including much of the information I’ve discussed in this post, plus a lot more.

The Paleo Approach by Sarah Ballantyne is a dense tome written by a scientist, chronicling in exquisite detail the complex workings of the human gut and how it interfaces with food and nearly every other system in the body.

The information is rock solid, and if you are dealing with any complex and recalcitrant health issues, you may well need the specifics that Ballantyne provides.

The information is rock solid, and if you are dealing with any complex and recalcitrant health issues, you may well need the specifics that Ballantyne provides.

The book is written for the layperson, but it is not an easy read. Explanations are comprehensive and extensive and detailed. The author covers every last tiny interaction that takes place in the intricate chain that permits molecules from food to pass through the intestinal membrane, and exactly how certain foods muck up the works for many people, especially the immune system.

I tend to use the index to research specific topics. I read paragraphs, even whole segments within chapters. But I rarely read an entire chapter at once, and I haven’t yet read the entire book from cover to cover.

It’s a great resource, but… 😉

For more from my blog on this topic, see:

Thinner and Healthier

Milk Is Highly Insulinogenic

Butter and Cream and Coconut, Oh My!

Why Seed Oils Are Dangerous

Why Calcium Isn’t Enough

2 •

2 •  5 •

5 •  9 •

9 •  12 •

12 •  14 •

14 •  15 •

15 •