My fates in Fate’s Door are spirits of time and thus less anchored within time as is everyone else. Many of the materials they weave into their tapestry of the world come from sources in the future or the distant past. Their loom is itself from the future, a vast floor loom in the style used by weavers of Nanjing brocade.

My fates in Fate’s Door are spirits of time and thus less anchored within time as is everyone else. Many of the materials they weave into their tapestry of the world come from sources in the future or the distant past. Their loom is itself from the future, a vast floor loom in the style used by weavers of Nanjing brocade.

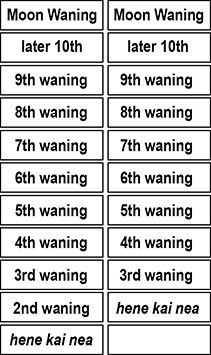

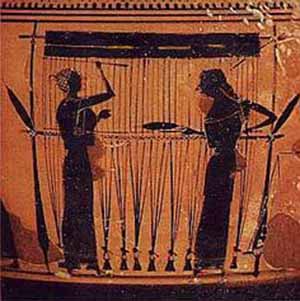

But Fate’s Door is set in the 4th century BC, which means that the peoples of the Mediterranean world are using vertical looms.

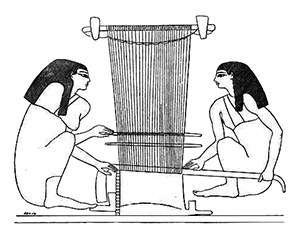

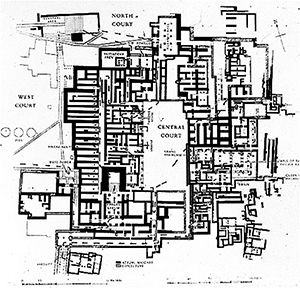

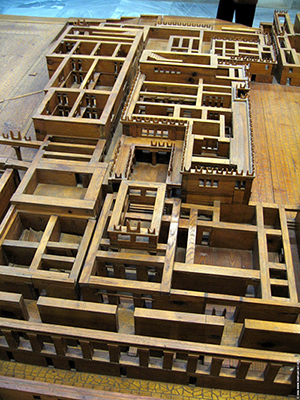

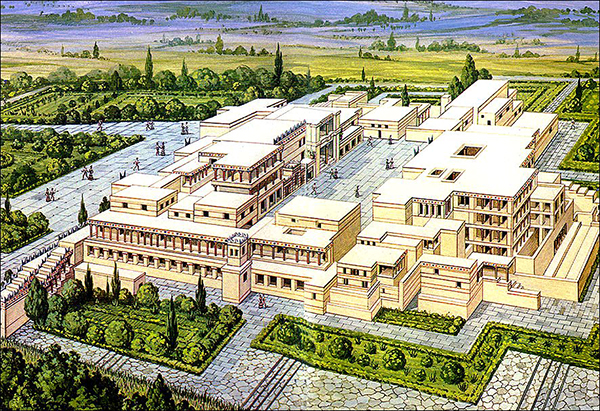

My heroine, the sea nymph Nerine, is familiar with the ground loom – the earliest loom developed, dating from 6000 BC – because one of her land dwelling friends prefers the ground loom. But when Nerine visits the land palace on Lapadoússa, she sees only vertical looms in use.

My heroine, the sea nymph Nerine, is familiar with the ground loom – the earliest loom developed, dating from 6000 BC – because one of her land dwelling friends prefers the ground loom. But when Nerine visits the land palace on Lapadoússa, she sees only vertical looms in use.

Now the scenes of my story, when they include work at a loom, feature only Calla’s ground loom and the massive beast of a loom at which the three fates weave. The vertical loom remains merely an offstage presence. But I wanted to know more about it, because it would set Nerine’s expectations for what a loom is and what she would imagine the fate’s loom to be.

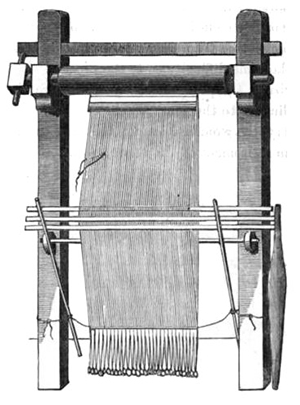

On a vertical loom, the long warp strands hang from a high bar which is supported by two sturdy posts. This frame can be upright and steadied by framed footings or leaned against a wall.

The warp threads themselves are kept taut by weights tied onto the end of each bundle of threads. Often extra thread might be wound around these weights. Since the cloth was woven from top to bottom, the weaver might wind the finished cloth around the top bar and then unwind more thread from each weight, allowing her to weave a cloth longer than the loom was high.

A heddle bar at roughly waist height allows the weaver to pull every other warp thread forward and then pass the weft thread across, with half the warp on front of it and the other half behind if. Moving the heddle bar back allows the foremost warp threads to fall back, creating an alternate “shed” through which to pass the weft.

Using a vertical loom required more strength than weaving at a ground loom, because the weaver must stand, she must reach up to weave the first portion of her cloth (a tiring position), and she must walk back and forth, if her cloth is wide.

Artemidorus Daldianus, a Hellene diviner of the 2nd century AD, said that dreaming of a vertical loom meant an upcoming journey, while dreaming of a ground loom or a backstrap loom meant rest. No doubt because of all the walking that weavers did during their days.

Artemidorus Daldianus, a Hellene diviner of the 2nd century AD, said that dreaming of a vertical loom meant an upcoming journey, while dreaming of a ground loom or a backstrap loom meant rest. No doubt because of all the walking that weavers did during their days.

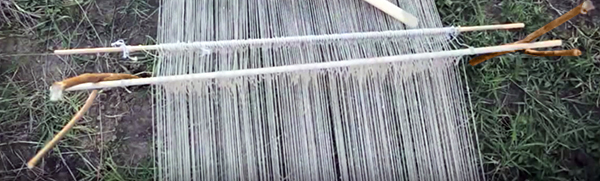

In the video below, the weaver (in ancient Hellene garb) is weaving a coarse cloth with coarse thread, but the ancients were capable of spinning their flax and their wool very fine. And their cloth of these threads or of imported silk could be a very high quality, especially if it was destined for the use of a wealthy household.

For more about the world of Fate’s Door, see:

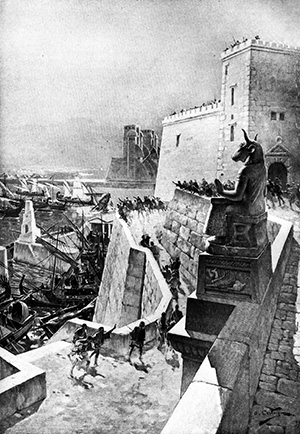

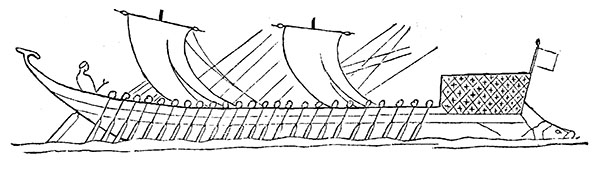

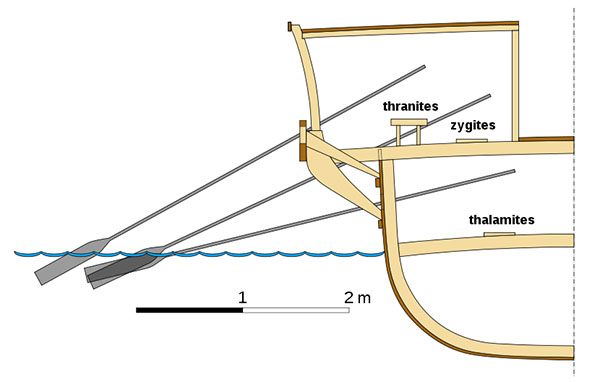

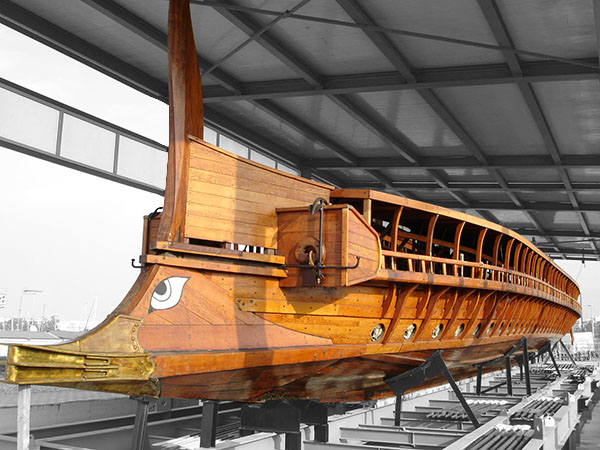

Warships of the Ancient Mediterranean

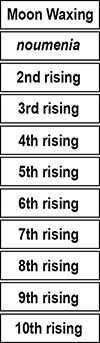

Calendar of the Ancient Mediterranean

Ground Looms

Lapadoússa, an isle of Pelagie

Merchant Ships of the Ancient Mediterranean

Garb of the Sea People

Measurement in Ancient Greece

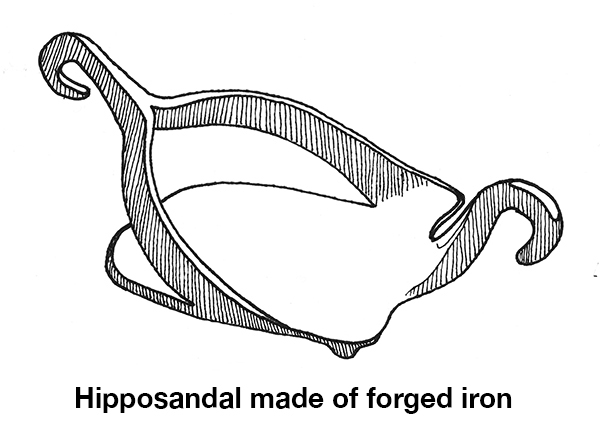

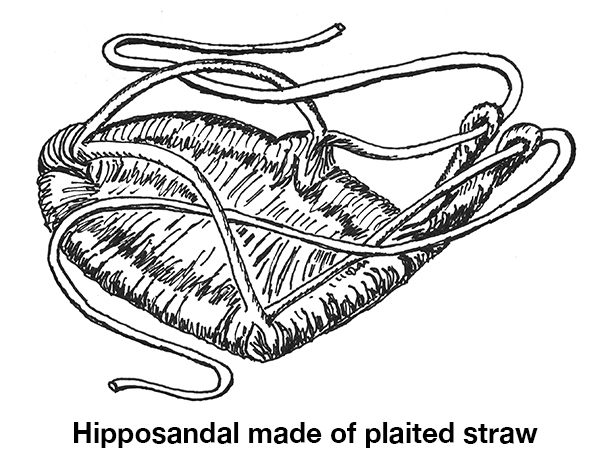

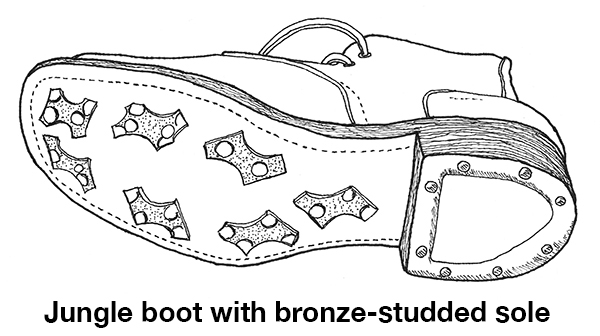

Horse Sandals and the 4th Century BC