Calico. Little House on the Prairie. Pioneer women.

Calico. Little House on the Prairie. Pioneer women.

These were the things that came to mind when I considered the domestic accomplishment of home canning.

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

(It still amazes me how easy it is to be wrong about things. Does that happen to you? Thinking you know, and then finding you don’t?)

So if canning is not a creation of the American West, where did it come from?

Napoleon.

Yes, Napoleon Bonaparte of the Napoleonic Wars. And, indeed, war was the inciting factor. The Napoleonic Wars saw the advent of mass conscription. With 800,000 soldiers in the field for 12 years, the French needed a way to feed their armies.

Yes, Napoleon Bonaparte of the Napoleonic Wars. And, indeed, war was the inciting factor. The Napoleonic Wars saw the advent of mass conscription. With 800,000 soldiers in the field for 12 years, the French needed a way to feed their armies.

The government offered a hefty prize to the inventor who could devise a way to preserve large amounts of food. Nicolas Appert – a confectioner and chef – rose to the challenge and won the prize.

His method?

Place the food in wide-mouthed glass jar. Force a cork tightly into the jar mouth using a vice. Seal it with sealing wax. Wrap the jar in canvas to protect it. Then dunk it in boiling water and boil it long enough to thoroughly cook the contents.

This was long before Pasteur and an understanding of microbes. But it worked.

This was long before Pasteur and an understanding of microbes. But it worked.

Appert’s method was adopted by the British armies, but transposed to wrought-iron canisters, which were cheaper to make and less fragile. Unfortunately, the can opener was not invented for another 30 years. The soldiers opened the cans with their bayonets!

Although canned foods spread into civilian households across Europe, they remained more a novelty item than a staple. The process was too industrial and expensive for home use.

That changed in the 1860’s when a tinsmith named John Landis Mason invented the Mason jar. It was a threaded glass jar with a matching threaded ring or band, a flat lid (held in place by the band), and a rubber ring that went under the lid for an air-tight seal.

People all over America and Europe started canning fruit, pickles, relishes, and sauces such as ketchup. These high-sugar or high-acid foods could be safely canned without the pressure canning that we know today.

(Vegetables and meats must be pressure canned to kill the deadly botulinum bacteria which thrives in low-acid, anaerobic conditions.)

When the 1880’s ushered in the widespread use of the cast iron stove, home canning reached new heights of popularity. The denizens of small towns were especially well-placed to take advantage of the new technology. They were close to the farms that produced the food, as well as possessing space for home gardens. And they had the cash to afford the jars.

When the 1880’s ushered in the widespread use of the cast iron stove, home canning reached new heights of popularity. The denizens of small towns were especially well-placed to take advantage of the new technology. They were close to the farms that produced the food, as well as possessing space for home gardens. And they had the cash to afford the jars.

Strawberry preserves, dill pickles, and apple butter abounded.

Home canning was a widespread practice by 1900 and rose to great prominence in America during both World Wars. By planting Victory Gardens and canning the harvest, citizens allowed the industrial machine to be aimed more efficiently at the war effort.

But, as you can see from this short history, canning is a relatively modern development.

So how did people preserve food before before the advent of canning?

And why did I delve into the history of food preservation in the first place?

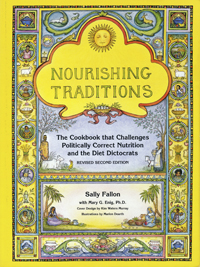

Well, I’ve been interested in one method of food preservation ever since I read the book Nourishing Traditions. The author, Sally Fallon, introduced me to the concept of lacto-fermentation. And it fascinated me.

Well, I’ve been interested in one method of food preservation ever since I read the book Nourishing Traditions. The author, Sally Fallon, introduced me to the concept of lacto-fermentation. And it fascinated me.

(You can read about my discovery in the blog post here.)

Even though I’ve eaten yogurt for decades, I’d had no idea that yogurt is technically lacto-fermented milk.

And I certainly didn’t know that you could lacto-ferment other foods besides milk.

If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, you’ve probably seen me write about this before. 😀

But if you’re new here, you might be asking, “What is lacto-fermentation?”

Lacto-fermentation happens when certain benign micro-organisms convert the glucose, fructose, and sucrose in food into lactic acid.

The micro-organisms are named – fittingly enough – after the substance they produce: they are lactobacilli. And they are present on the surface of most living organisms.

All they need to produce lactic acid is an anaerobic environment (a finger-tight jar) and a moderate “climate” (temperatures between 70 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit).

And the process itself is really pretty nifty.

As the lactobacilli produce lactic acid, the acidity of the food rises. As the acidity rises, most other bacteria, including those that cause spoilage or disease, are killed.

The lactic acid curdles milk, to make that nice custardy texture of yogurt.

The lactic acid combines with the molecules of cabbage (and other vegetables) to form esters, which gives sauerkraut its unique flavor.

The lactic acid combines with the molecules of cabbage (and other vegetables) to form esters, which gives sauerkraut its unique flavor.

The lacto-fermentation process increases the bioavailability of vitamins and other nutrients, making lacto-fermented foods more nutritious than the original raw vegetable.

Plus the live cultures present in lacto-fermented foods help keep the human gut well-populated with beneficial micro-flora.

Bottom line?

Lacto-fermented foods are safe. They store unspoiled for a long time.

Lacto-fermented foods are delicious. Lacto-fermented cabbage is so much tastier than cabbage pickled in vinegar!

And lacto-fermented foods are good for you.

Why did we ever forget about them? I don’t know. But I do know that my new knowledge came in handy while writing stories set in my North-lands!

Why did we ever forget about them? I don’t know. But I do know that my new knowledge came in handy while writing stories set in my North-lands!

I wrote Troll-magic before I learned about lacto-fermentation. Since the technology level in Troll-magic is roughly equivalent to our own Steam Age, I assumed home canning was the norm in most households. I didn’t delve into the details of Lorelin’s kitchen, but she did pack up dried meat and dried pears, when she left home. (Drying is a very, very old method of food preservation.)

The technology of her culture undoubtedly could have supported home canning. And she lives in a time of peace following an extended time of warfare and mass conscription. (The wars in which the Giralliyan Empire gobbled many of it’s smaller neighbors.)

But, now that I do know about lacto-fermentation, I like to think that the people of the North-lands never abandoned it. I feel sure that Lorelin’s mother had shelves of lacto-fermented cabbage and turnips and greens and onions in her pantry. Yum!

Luckily, I had discovered lacto-fermentation before I wrote Sarvet’s Wanderyar. Because I was very clear that the Hammarleeding culture did not have the technological sophistication to support home canning. They would have had to get by with drying food, freezing it (during the winter months), salting it, curing it with smoke, and eating cooked dishes quickly, before they could spoil.

Luckily, I had discovered lacto-fermentation before I wrote Sarvet’s Wanderyar. Because I was very clear that the Hammarleeding culture did not have the technological sophistication to support home canning. They would have had to get by with drying food, freezing it (during the winter months), salting it, curing it with smoke, and eating cooked dishes quickly, before they could spoil.

I was very happy to know they had another option! And we see that option pretty promptly when Sarvet teases her friend Amara with a platter of gundru – lacto-fermented greens.

So why did I read up on the history of canning?

I was mulling over my writing good luck a few weeks ago, and I got curious. Given that lacto-fermentation is so handy and yummy, how did the canning process get started?

I did some investigating. And you know the rest: I had to share! I hope you found the journey interesting. 😀

For more about lacto-fermentation, see:

Amazing Lactobacilli

Lacto-fermented Corn

For more about Lorelin and her world, see:

Character Interview: Lorelin

North-land Magic

A Great Birthing

For more about the world of the Kaunis-clan, see:

What Is a Bednook?

The Kaunis Clan Home

Hammarleeding Fete-days

Why Did the Three Goats Cross the River?

Livli’s Family

Ivvar’s Family

Pickled Greens, a Hammarleeding Delicacy

And for more about the history of canning, see these external links:

A Brief History of Home Canning

Commercial Canning

Nicolas Appert

John Landis Mason

When I wrote the story Resonant Bronze, I needed to know more about gongs.

When I wrote the story Resonant Bronze, I needed to know more about gongs. This is one of those times I was super glad I’d done my research! It would have been so easy to get this wrong. My natural inclination is to research topics I don’t know much about. I just don’t feel comfortable writing my story when there’s an important element in it and I’m ignorant. Of course, it’s not just wanting to get the details right that propels me. I’m also insatiably curious! 😀

This is one of those times I was super glad I’d done my research! It would have been so easy to get this wrong. My natural inclination is to research topics I don’t know much about. I just don’t feel comfortable writing my story when there’s an important element in it and I’m ignorant. Of course, it’s not just wanting to get the details right that propels me. I’m also insatiably curious! 😀