Lugh or Lú was a Celtic god with a long pedigree. He was part of Irish mythology in pre-Christian Ireland, that is, the centuries before 400 AD.

Lugh or Lú was a Celtic god with a long pedigree. He was part of Irish mythology in pre-Christian Ireland, that is, the centuries before 400 AD.

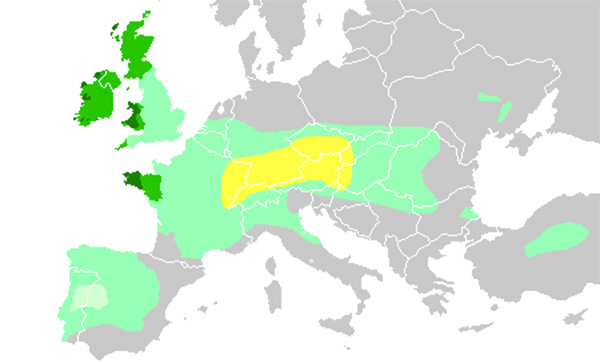

But the Celts arrived in Ireland around 275 BC, bringing their culture and their religious beliefs with them, including Lugh.

The god’s name gives some indication of his journey through time.

The Celts in Gaul and Iberia called him Lugus. The syllable “lo” in Apollo may indicate some connection between Lugh and Apollo, especially because the Indo-European root word of leuk means “flashing light,” and Lugh is believed to derive from leuk.

Yet the meaning “flashing light” seems more likely to refer to lightning than the sun. Indeed, the Breton luc’h and the Cornish lughes both mean “lightning-flash.” (Lugh may have been a predecessor to the Norse god Thor.)

Of even more interest to me was the well-established fact that the Gaulish Lugus was considered by the ancient Romans to be the Gauls’ version of Mercury. Mercury was the patron god of commerce, contracts, eloquence, messages, travelers, and trade.

While the Gaulish Lugus was a master of all arts and oversaw journeys and business transactions.

These mentions of Lugus and Mercury occurred during the time of Julius Caesar in the 1st century BC, roughly 280 years after the events in Fate’s Door. The thing is, while the ancient Greeks of the 4th century BC make mention of the Keltoi, they do not describe the Keltic religious beliefs. I was going to have to do some extrapolating.

My first decision: Lugh’s name. The western Celts in later periods seemed to move toward the ending sound of “g” as is given or “ch” as in chosen. How might the pronunciation of earlier Keltoi who moved east to settle have changed? Did they stay with the “k” sound from from leuk?

Since I really had no true indication – I’d have to guess – I decided to stick with the name used in pre-Christian Ireland, Lugh, rhyming with Hugh. Perhaps we moderns might have spelled the name of my 4th century BC Keltic god as Leu. But I decided to keep it simple. So, Lugh.

Since I really had no true indication – I’d have to guess – I decided to stick with the name used in pre-Christian Ireland, Lugh, rhyming with Hugh. Perhaps we moderns might have spelled the name of my 4th century BC Keltic god as Leu. But I decided to keep it simple. So, Lugh.

There are many stories about Lugh in Irish mythology, but the one that caught my attention concerned Lugh and his foster mother Tailtiu. Tailtiu was the goddess who cleared the plains of Ireland for agriculture.

What if this were a very old story that traveled with the Celts as they left central Europe and was modified to relate to their new surroundings? I could imagine the myth as originating in the lands along the Danube river, where Lugh’s foster mother cleared the plains of what is now Hungary and Romania for agriculture.

Like the Hellenes who created lesser gods associated with local springs and valleys (in addition to their supreme Olympians), so did the Keltoi revere local features. And the most dominant nature goddess would have been Danu, the spirit of the mighty Danube river.

Therefore I mapped the story of the Irish Lugh onto the territories of the Keltoi.

In the 4th century BC of Fate’s Door, Lugh was fostered by Danu. Like the Irish Tailtiu, Danu was exhausted by her labor and unable to fight off the demons of blight and famine. Her son Lugh fought in her stead to preserve his mother’s legacy, but he was overcome and imprisoned. Yet just as the stalk of grain is cut down and springs renewed from the earth after its seed is planted, so does Lugh prevail. He rises to new strength after his capture, defeating the demons, and then presiding as sovereign over the agricultural cycle of fertility.

The Irish Celts celebrated Lugh in a festival that marked the beginning of the harvest season, around the beginning of August. This was the Lunasad, which included visits to nearby holy sites, athletic contests, dance, feasting, trading, and a ritual play enacting Lugh’s fight against the demons of blight and famine.

I decided that my Keltoi would celebrate a similar festival. As it happened that Nerine – the heroine of Fate’s Door – would arrive at the stronghold of the Keltic High King in early August, she would naturally participate in that festival. The dancing, the feasting, and the High King’s courtesy to her would delight Nerine, but one of the religious rites would disturb her deeply and propel her further along her inner journey.

I decided that my Keltoi would celebrate a similar festival. As it happened that Nerine – the heroine of Fate’s Door – would arrive at the stronghold of the Keltic High King in early August, she would naturally participate in that festival. The dancing, the feasting, and the High King’s courtesy to her would delight Nerine, but one of the religious rites would disturb her deeply and propel her further along her inner journey.

Early in my research on the Keltoi, I learned of the connection between Lugus and Mercury and decided that a similar connection existed between Lugh and Hermes. Hermes, as the patron of orators, poets, athletes, invention, travellers and trade, would possess a similar affinity to Lugh. It also worked beautifully with my choice for Nerine to travel across Europe under the protection of an elite cohort of Hermes’ warriors.

For more about Nerine’s world, see:

The Keltoi of Európi

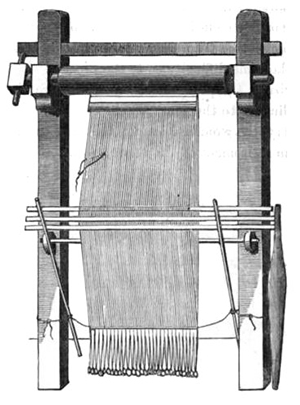

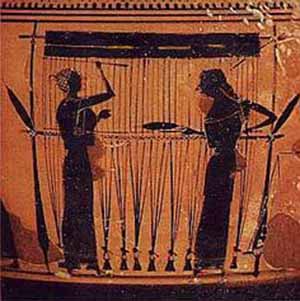

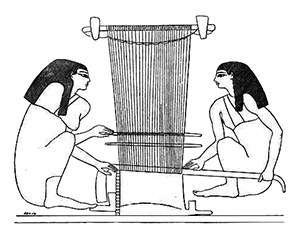

Vertical Looms

Names in Ancient Greece

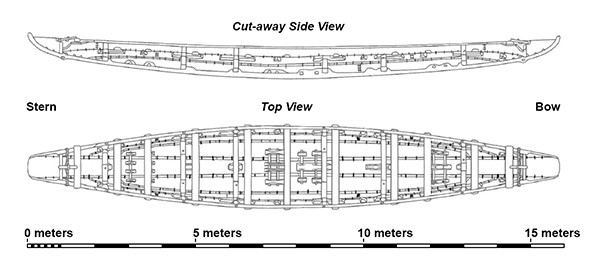

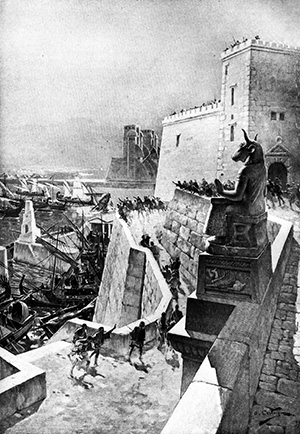

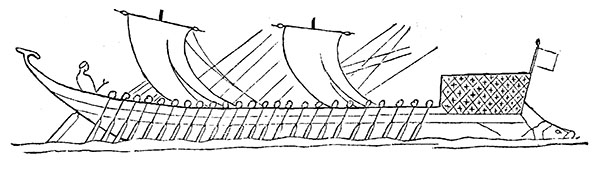

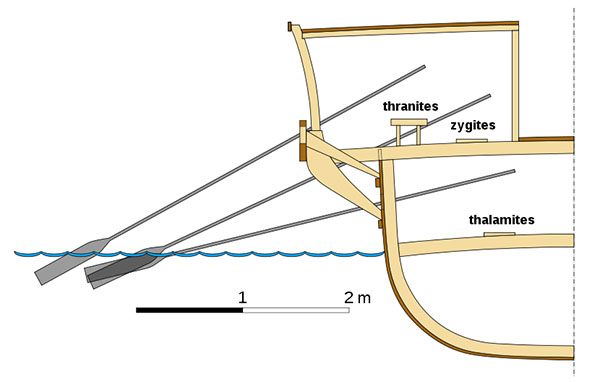

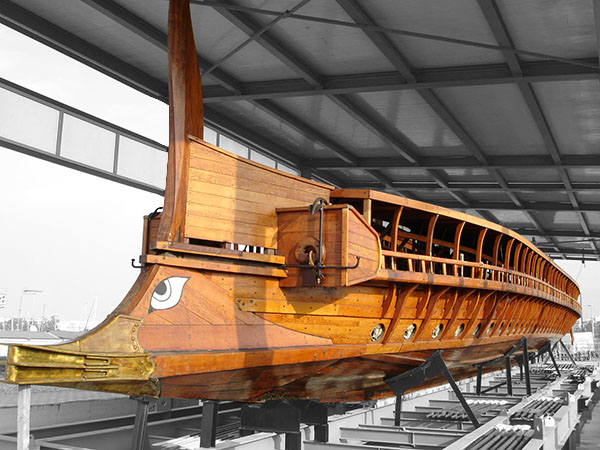

Warships of the Ancient Mediterranean

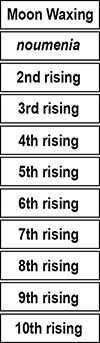

Calendar of the Ancient Mediterranean

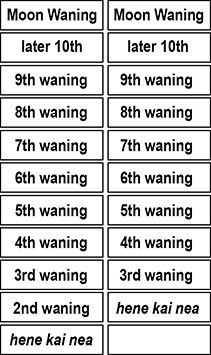

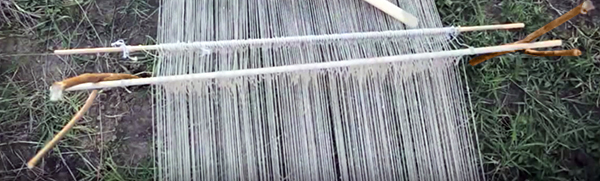

Ground Looms

Lapadoússa, an isle of Pelagie

Merchant Ships of the Ancient Mediterranean