The Muses of the ancient Greeks were goddesses of the knowledge embodied in poetry, song, and story. They served as sources of inspiration for science and the arts. Their number varied throughout history, but I chose the classical nine to appear in my novel blending Greek mythology with ancient history, Fate’s Door.

The Muses of the ancient Greeks were goddesses of the knowledge embodied in poetry, song, and story. They served as sources of inspiration for science and the arts. Their number varied throughout history, but I chose the classical nine to appear in my novel blending Greek mythology with ancient history, Fate’s Door.

Calliope – the muse of epic poetry and eloquence, with her symbols of stylus, writing tablet, and lyre. Epic poems were long, recited narratives on serious subjects, describing heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or city-state. Epic poetry possessed greater status than other types of poetry.

Calliope – the muse of epic poetry and eloquence, with her symbols of stylus, writing tablet, and lyre. Epic poems were long, recited narratives on serious subjects, describing heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or city-state. Epic poetry possessed greater status than other types of poetry.

Clio – the muse of history, with her symbols of scroll and tablet.

Euterpe – the muse of music, song, and elegiac poetry, with the aulos (similar to a flute) as her symbol. In ancient times, elegy was always sung and accompanied by the music of the aulos. It required a specific rhythm and form, but was not limited to lament in content, as it is today. Elegiac poetry was always sung and accompanied by flute music.

Erato – muse of lyric poetry, with the cithara (similar to the lyre) as her symbol. Lyric poetry expressed personal emotions and was in the first person, I. Lyric poetry was always sung and accompanied by strummed music.

Erato – muse of lyric poetry, with the cithara (similar to the lyre) as her symbol. Lyric poetry expressed personal emotions and was in the first person, I. Lyric poetry was always sung and accompanied by strummed music.

Melpomene – the muse of tragedy, with her symbols of tragic mask, sword, club, and boots.

Polyhymnia – the muse of sacred poetry, sacred hymn, sacred dance, meditation, and geometry, with her symbols of veil and grapes.

Terpsichore – the muse of dance, with her symbols of the lyre and plectrum, played for dancing.

Thalia – the muse of comedy and idyllic poetry, with her symbols of comic mask, bugle, trumpet, shepherd’s crook, and ivy wreath. Idyllic poems were short descriptions of the small, intimate world of personal experience.

Thalia – the muse of comedy and idyllic poetry, with her symbols of comic mask, bugle, trumpet, shepherd’s crook, and ivy wreath. Idyllic poems were short descriptions of the small, intimate world of personal experience.

Urania – the muse of astronomy, with her symbols of globe and rod.

One of the scenes I cut from Fate’s Door features the continuous “party of the arts” which is life with the muses on Mount Helicon. Anippe, the youngest sister of my protagonist Nerine, tends the spring of inspiration patronized by the muses, and thus serves as an inspiration to inspiration. 😀

19 ~ Agnippe and the Muses

Later in the day, when Nerine met the muses, she discovered they were just as impressive as the gods of Olympus, but in a very different way.

She’d donned her long green silk gown again – dry from hanging on a rose bush in the sunlight – and Agnippe had changed from her belt and pectoral to a knee-length gown of rose silk. She carried a tray bearing a ewer of spring water and nine chalices of varying design.

The muses were gathered on the stage of an intimate amphitheater, with stone seating cut into the mountain, and a simple colonnade as a backdrop. Euterpe, the Muse of Song, stood on a pedestal singing. She wore a long, draping gown of marigold yellow, and her honey-hued hair was elaborately braided and pinned.

But Nerine, entering the stage from one side with Agnippe, barely noticed the charming picture before her. Euterpe’s voice soared, golden and mellow in its lower notes, silver and sweet in the higher ones.

Nerine felt the world turn within her, deep in her heart, while the sky shivered into rainbow streamers, as though the whole of creation sang.

She returned to herself only when Euterpe ceased her song.

The gathered muses – some leaning against the pillars of the colonnade, a few seated on the stage flagstones, others clustered around Euterpe – signified their approval in differing ways according to their natures.

Only one clapped her hands together and laughed: a blonde garbed in a rose slightly lighter than that Agnippe wore. Might she be Thalia, the Muse of Comedy?

An aqua-gowned muse wiped tears of joy from her cheeks. A lilac muse gazed raptly at the sky. The Muse of Astronomy? And a peach muse circled Euterpe in graceful dance steps.

All of them exuded the glory that imbued their arts – a nimbus of exaltation and brightness that quickened the pulse and flushed the cheek. Nerine felt more overborne by it than she had by the potency cloaking the greater gods. If Hera were a spring tide – massive and inexorable – then the muses were a fountain bursting from the earth in joy and abandon.

Euterpe, the golden singer, caught sight of Agnippe and Nerine first. She leaped lightly down from her pedestal, exclaiming. “Sisters! The bearer of our inspiration approaches!”

Her quick steps toward them were graceful enough to be a dance, and her sister muses streamed after her, all of them clustering around Agnippe and speaking at once.

“What draught have you now for us?”

“Is this the Nerine you have spoken of?”

“Hidden in the daybreak by Helios, the great Karkinos ascends, blessing all who travel north!”

“Nerine” – the peach muse grabbed Nerine’s hand – “you look born to perform the pidiktos, the leaping dance! May I teach you?”

“Introduce us!” chimed a muse in pale green.

Agnippe laughed and passed through the throng, drawing Nerine and the peach muse with her, to the pedestal abandoned by the singer Euterpe. She set down her tray there and began pouring from the ewer into the various chalices, using a different grip on the ewer’s handles for each to produce different shapes in the stream of water.

“The silent wisdom of the Karkinos for you, Urania.” A silver chalice set with amethysts went to the lilac-gowned muse.

“A new melody for you, Euterpe!” In a golden chalice adorned by topazes.

“A variant rhythm for you, Terpsichore.” The peach-garbed muse holding Nerine’s hand received a copper chalice, shaped to resemble an opening bud.

The blended voices of the muses sounded like the ripple of a musical brook, but their speech quieted as each received her cup from Agnippe and sipped.

Into the growing silence Agnippe presented Nerine. “Please welcome Nerine Merenou Pelagieus, my sister and my friend. She has traveled from the heart of the Middle Sea and has yet farther to go.”

Each of the muses paused in her sipping to raise her chalice in her own characteristic way – overhead, subtly tilted, to eye level, and so on – and spoke a blessing.

“Be at home, here and in yourself.”

“May you seek inspiration each morning and find delight as the sun sets.”

“Remember to laugh!”

“It is well to journey north under the ascendance of the Karkinos.” That was the lilac-gowned muse again. Her preoccupation with the zodiac must mean she was the Muse of Astronomy, guessed Nerine.

As the afternoon blended into the golden light of a summer evening, Nerine decided that the muses threw a much better party than the gods. Not that this was truly a party. It seemed to be the natural order of life on Mount Helicon.

Formality was entirely absent, one activity flowing into another without plan or pomp, according to chance and what caught the muses’ fancy.

They sang roundels under golden Euterpe’s guidance and then engaged in impromptu comedic drama with rosy Thalia. Nerine found herself singing in parts with neither worry nor trouble, and then devising a sequence of slapstick humor.

Terpsichore – the peach one – led them to the meadow beyond the topmost tier of the amphitheater to dance, and Nerine found herself performing the leaping pidiktos, as promised, with only one stumble when she forgot – in mid-air – that she was not suspended in water. Then Polyhymnia called for an interval of meditation before a hymn.

As the sky deepened from rich turquoise to a deep cobalt which seemed to reach beyond the edge of the earthly sphere, a light breeze sprang up. Nerine found herself walking through a birch forest – its leaves arustle with the moving airs – beside Clio, the Muse of History, and chatting with her as though to a lifelong friend.

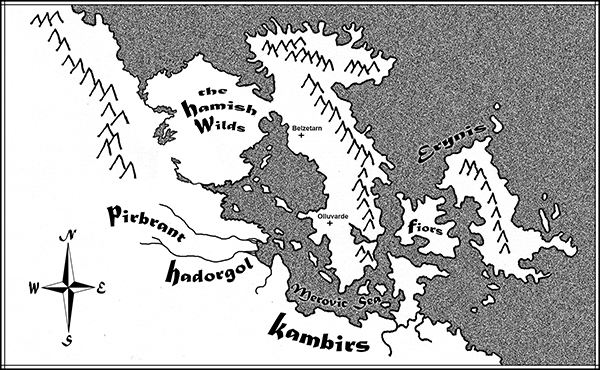

“You’ll have such opportunities as you travel north,” said Clio seriously. “The customs of the Keltoi and the Gutones are very strange, quite different from those of the Hellenes. Request papyrus and ink from Lord Hermes that you may record the marvels you see!”

A pang of grief and loss shot through Nerine’s breast. Just so had Altairos promised to record all the experiences of his travels, but she had curtailed his chance to share them with her. Should she now compile a similar history that she would never share with him? Perhaps the symmetry of it would balance . . . something.

When she emerged from the birch grove, the stars shone in the deepening sky, and Urania had arranged a cluster of spyglasses that the muses and their guest might view the planet Hesperus at the peak of its splendor, gleaming like a teardrop kindled by fire.

As Nerine withdrew her eye from her spyglass, the shepherd youths who had greeted her upon her descent from the pegasus were present again, spreading tapestries over the meadow grasses, and serving supper.

The scent of crushed grass mingled with the savory aromas of roast lamb and the lighter fragrances of berries.

More vignettes of culture – an epic poem, a tragic drama – followed the meal. Nerine participated as before, comfortable and welcomed, but she found a sliver of her attention pursuing her sister. Agnippe was radiant, partaking of everything, but also consulted by the muses. Might this arpeggio be better if extended another beat? Would that rhyme be more effective if moved to the middle of the line rather than falling at the end?

Agnippe filled her post on Helicon just as surely, just as joyously, as Eilidh occupied hers on Olympus.

Nerine gave herself over to happiness for a time. Enjoying the rapture of the night, and enjoying the awareness that two of her sisters were happy. Life could bring gifts to those who were open to them. Good fortune might yet bless her too. But she wouldn’t think about herself tonight. She would be here and now, beguiled by the moment and rejoicing for Eilidh and Agnippe.

Despite her focus on her sisters, she’d gotten herself back, she realized. The sense of self she’d lost on Olympus had returned here on Helicon.

She was wholly Nerine again, inside and out. The Nerine who loved her youngest sister. The Nerine who loved new things and new places and meeting new people.

That Nerine was back and it felt as glorious as Euterpe’s song, as Terpsichore’s dance, as Urania’s star gazing.

It was wonderful to be herself again.

But had she lost something else in the reclaiming of herself?

What had she lost? For she had lost something.

A softening – like a mist – rose up behind her, obscuring all that was neither Olympus nor Helicon. Her past seemed as far away in time as the reef palace was in distance. Had she really dwelt all her life in the Middle Sea? Traveled only so far as Duke Thiago’s palace in the Gulf of Gallicus? Gone ashore only on the isle of Lapadoússa?

It seemed a dream, not a history, and it had happened to someone other than her.

Had she really met and fallen in love with a prince of Zakynthos and then renounced him? A stab of pain through her heart assured her that she had.

But the sense of detachment piling up around her memories draped a veil over them, lessening their immediacy. For now, she was not Nerine of the Middle Sea, but Nerine of Helicon. And being Nerine of Helicon was delightful.

Later in the night, she found herself with Agnippe, curled on a pile of softest fleece under an arching trellis covered with blooming honeysuckle. The sweet, sweet scent of the vines drenched her, and the darkness wrapped her round as gently as water from a warm spring.

“Is it always like this?” Nerine murmured.

Agnippe chuckled. “Nearly always. Some days the work is more like work. When Calliope cannot settle on the right meter for her epic nor Melpomene devise the right dramatic beat for her tragedy. But work more usually masquerades as play, and the play is the work.”

“I wish I could stay here,” said Nerine. Except she didn’t. Not truly. “I wish I could be you. Or one of them.” That she did wish, but knew – in spite of the wish – that she would be less than herself, if her wish could become reality.

Agnippe shifted on her portion of the fleece cushioning. “No, you don’t.”

“This afternoon and this evening have been . . . magical.” Nerine felt drowsy and hyper aware at the same time. Did the arts always produce an altered state? Perhaps only when the muses performed.

Agnippe found Nerine’s hand and clasped it loosely in hers. “The magic of the muses is extraordinary, but you have your own magic, Nerine. And you won’t develop it here. I think you are right to go to the norns. I think . . . you will be surprised by what awaits you there.”

Unease threaded Nerine’s contentment. “Do you know something I do not?” she asked.

“I know nothing,” said Agnippe, “but I have an intuition that it will all be different than what you expect, and that the difference is exactly what you need. Even though I don’t know what you need, and you don’t know what you need – just like Xianthe – it will come to you.” Agnippe’s voice was a mere breath, soft and low. “Or you are going to it.”

The late moon, very full, rose above the shadowy treeline edging the glade around the trellis. Dapples of moonlight peeped through the honeysuckle, speckling Nerine, her sister, and the fleeces beneath them. A breeze moved the leaves and the pattern of moonshine. The heavy fragrance of the flowers – almost too sweet – lightened.

“Still no word from Xianthe?” asked Agnippe.

Nerine refused to be worried in this haven of peace. Eilidh and Agnippe had come home to themselves. The promise of the same – or something even more astonishing – awaited Nerine. Surely Xianthe would find her way too.

“No word,” said Nerine. “But the fates spin her thread as surely as they spin ours.”

Agnippe laughed, soft and clear. “And you go to the fates. Perhaps you will spin Xianthe’s homecoming.”

Perhaps she would.

* * *

Bidding Agnippe farewell the next morning was both harder and easier than Nerine expected.

She’d loved her brief stay on Helicon. Loved it! The muses were delightful, and their idea of fun was actually fun. But she sensed that the arts were not really the home her spirit sought. She might be distracted by bliss, if she were to live here, but she would not find the deeper anchoring that meant more to her.

She could leave Mount Helicon quite calmly.

But Agnippe! Oh!

Her sister had resumed belt and pectoral – this set fashioned of linked plates of swirling green malachite – because she would be tending the sacred spring after Nerine’s departure. She was a slim sylph of a girl, with the modest curves of the almost-fifteen that she was, but with strength in her carriage.

Her face showed a curious mix of emotion – lips trembling in her sadness at parting from Nerine, green eyes serene with her confidence in Nerine’s future and lit with the excitement that working in her spring brought.

Nerine hugged her convulsively. She would not see Agnippe for years. Five years? Ten years? Agnippe would be all grown up when Nerine visited her next. Would they still know one another?

“We’ll always be sisters,” Agnippe whispered, “always friends. You will know me, and I, you.”

Nerine relinquished her hold on her sister enough to see her eyes. How was it that Agnippe often seemed to read her mind? Nerine studied Agnippe’s face. Agnippe knew how to trust both herself and her future.

Agnippe’s trust would have to be enough for Nerine too, because Nerine . . . had no trust in herself at this moment.

“I love you,” Nerine said.

Agnippe smiled. “I love you too.”

And then Nerine was following the shepherd boys down the mountain to the meadow where she would mount the pegasus.

She looked back once.

Agnippe stood in the distance at the top of the slope, very straight, the sun turning her long green-blond hair to gold. She raised her arm in farewell. Nerine returned the gesture and turned away, rounding a bend in the path that removed Agnippe from sight.

Nerine drew in a shaky breath.

* * *

For the next extra chapter from Fate’s Door, see:

Hera’s Handmaidens (Eilidh’s Farewell)

For the first two extra chapters from Fate’s Door, see:

Update on Fate’s Door (Eilidh and Mount Olympus)

Nerine’s Youngest Sister (Agnippe and Mount Helicon)

To purchase and read Fate’s Door: Amazon I B&N I iTunes I Kobo I Smashwords