Crawling around the privy smithy bearing one of Arnoll’s tallow dips, Gael collected fully as much dirt and soot on his tunic and trews as he’d expected. The smithy scullions kept the forge area clean and tidy. The tower sweeps kept the floors and counters clear. But the odd corners, crevices between various fixtures and the wall, and the surfaces below the tool racks collected finely sifted ash ground into grease.

Crawling around the privy smithy bearing one of Arnoll’s tallow dips, Gael collected fully as much dirt and soot on his tunic and trews as he’d expected. The smithy scullions kept the forge area clean and tidy. The tower sweeps kept the floors and counters clear. But the odd corners, crevices between various fixtures and the wall, and the surfaces below the tool racks collected finely sifted ash ground into grease.

It had never occurred to Gael that he should squirm on his belly under the lip of the privy forge or squish between the counters and the back wall, but now that he had, he would develop a few additional protocols for smithy maintenance. He should probably first check the other smithies to see if they suffered the same pattern of encrusted dirt. They might not.

Arnoll found a set of elegant two-tined forks in an empty quenching pail. Who knew which day they were forged? Gael himself found nothing. And neither of them discovered any missing ingots.

When Arnoll closed the lid of a chest of sand with a snap, Gael shook his head. “I think we both knew there was nothing to find,” he said. “But I had to check.”

Arnoll surveyed the blackened knees of his trews ruefully. “The leather grooms are going to beat me senseless when I hand these over for cleaning,” he remarked.

Gael’s knees were no better. “Time to quit for tonight, I think,” he said.

Arnoll nodded and led the return to the counter in his smithy where the stolen copper ingot still rested. Gale collected it, and then they headed for the exit on the back wall where the Cliff Stair climbed to the magus’ quarters below the battlements.

Gael was glad for his tallow dip, burning low at this point though it was. The torches in the tunnel between the smithy and the stairwell were doused, as was usual at this hour. And so few trolls climbed the Cliff Stair at night that only every third landing was illuminated by a flaming torch. Gael wasn’t sure why Theron bothered to order any torches lit. The bright landings merely meant one’s eyes must work harder to adjust on the dark ones and all the dark steps in between.

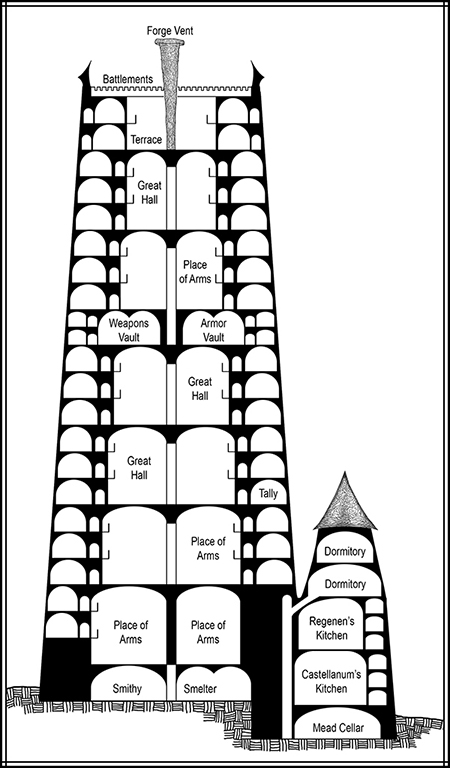

In silence, Gael climbed side by side with Arnoll, past the place of arms adjacent to the melee gallery and on toward the place of arms on the next level. His thighs felt weak as pouring copper, and his left ankle stabbed fiercely each time he took the next tread with his left foot. He’d chosen the outer position, which required longer steps, to spare Arnoll. Now he wished he hadn’t. Arnoll hadn’t climbed up and down the tower all day the way Gael had.

As they rounded the newel post toward a landing that should have been bright with flickering torch flame, Gael put out a hand to check Arnoll.

The landing was dark.

Gael paused, listening.

The sound of a door closing softly somewhere above was followed by the click of a latch, a gasp, and then running footsteps, headed up. Someone—perhaps the someone who’d doused the torch—had noticed the glow of their tallow dips approaching.

Gael looked sharply at Arnoll. Arnoll looked back, nodded.

And then they were running, shoving their weary bodies upward with all the speed possible. Whoever it was had a guilty conscience. They’d catch him, question him, and find out why.

Reaching the dark landing brought momentary relief to Gael’s tiring legs—three full strides across a blessedly flat floor. Then they were climbing again, up and up, around and around.

Gael felt his pace slowing, heard the furiously echoing steps of their quarry drawing away. He pushed harder, but sheer will wasn’t enough to hasten his faltering feet.

The footsteps above quickened, then cut off altogether.

Gael cursed and halted, slumping against the outer wall of the stairwell. Arnoll stopped a few steps above him, equally winded.

“He’s left the stair,” panted the smith.

Gael nodded, bent with one hand on his knee, sweatily clutching his copper ingot, the other holding his tallow dip, lungs heaving.

“Hells,” said Arnoll. “A dozen deep-set doorways, the central stair, half a dozen dark embrasures, and the entrances to the three other stairwells. We’ll never catch him.”

That was a given, now that they’d broken off the pursuit. But Gael shared Arnoll’s unspoken conclusion. Their fugitive could be anywhere by now.

Gael hung there, catching his breath. His grubby tunic clung to his shoulders and back as though someone had dumped a bucket of quenching water over him. His ribs ached, and his arms wobbled almost as badly as his legs.

“Let’s go see what’s behind that door just above the dark landing,” he said at last, straightening. “A latrine, I think. But.”

Arnoll nodded.

Gael’s panting had slowed, as had Arnoll’s. They waited several moments more. Descending on wobbly legs would be worse than climbing.

“Come,” said Gael, starting down, taking the inside position this time.

Arnoll joined him with a grunt. “I almost wish I owned a cane,” he muttered.

Gael snorted a laugh. Arnoll with a cane was ludicrous, but Gael wanted one, too. Each step down to the next tread threatened to collapse his legs entirely. Had his troll-disease advanced another notch? Or did he merely sit too long every day at his tally desk?

When they reached the door located three steps above the dark landing that should have been bright, Gael eased it open. A powerful stench rolled out.

There was indeed a latrine behind that door, with the usual arrangement: a square of stone floor, a closed stone bench at the back, a round hole carved in the seat of the bench, and a slanting ceiling overhead.

So much was ordinary.

The wastes brimming at the lip of the latrine hole were not.

The latrines located off the Cliff Stair emptied into long channels descending through the walls of the tower, carrying their contents to the steep cliff located on this side of the citadel. The channel emptying this latrine—like several others—possessed a dogleg and required regular maintenance to prevent clogging. Such maintenance was always scrupulously provided, never neglected. Why had it been neglected now?

Gael reeled back, jostling Arnoll and nearly tumbling both of them down the two steps to the landing.

Somehow, Arnoll retained his balance, steadying Gael as well.

“Sias!” gasped Arnoll.

Gael surged forward to close the door. It didn’t reduce the stench much, and they retreated to the next landing up, where an arrowslit provided fresh air. Their tallow dips flickered wildly.

“What in hells?” said Gael.

Arnoll shook his head.

Gael pressed his lips with a forefinger, thumb beneath his chin. “Someone didn’t want to be discovered there.” He thought a moment, resisting what came next. “I’m going to check it thoroughly.” If only he’d not doffed his caputum when he changed his clothes. He could have pulled the fabric that covered his shoulders up over his mouth and nose.

“Wait here,” he told Arnoll, handing him the copper ingot.

The smith chuckled. “Oh, I’m coming with you,” he said.

“You need not.”

“Oh, I know, I know. But I’m curious, too.”

The stench outside the latrine door had not dissipated appreciably. It strengthened unpleasantly when Gael opened the door. He buried his mouth and nose in the crook of his elbow, held his tallow dip high with the other arm, and stepped inside, Arnoll hard on his heels.

Surprisingly, the floor was clean and dry, as was the surface of the bench.

Why had the castellanum’s scullions cleaned the latrine compartment thoroughly, but left the clog untouched? Surely they’d earn a birching that way.

Gael studied the slanting ceiling behind the bench, the small blocks of stone neatly fitted together, the mortar between them tidy. The side walls were similar. The front wall possessed a small arched niche to one side of the door, with a bucket of water resting within.

Gael removed the bucket, handing it to Arnoll, who set it down on the bench, well away from the brimming hole.

Gael crouched, hampered by the cramped space, peering into the empty bucket niche. His tallow dip flickered and went out, but he waved aside Arnoll’s offer of his, setting the extinguished saucer on the floor and probing the niche with his freed hand.

The mortar felt crumbly and loose. He worked a piece out, held it up in the dim light of Arnoll’s dip, then put it down to pick at the loose mortar again. Following the seam, he discovered a section lacking mortar altogether. His fingertips traced out a rough rectangle. He probed for purchase, then drew out the unmortared stone.

“Hah!” Arnoll exclaimed.

Gael stayed grimly silent, reaching into the now open cavity in the niche’s sidewall.

Somehow, he felt entirely unsurprised when he pulled out two nested ingots of bronze.

Next scene:

The Tally Master, Chapter 6 (scene 30)

Previous scene:

The Tally Master, Chapter 6 (scene 28)

Need the beginning?

The Tally Master, Chapter 1 (scene 1)

1—Front Room

1—Front Room