So, what is a lodestone?

In the real world, it’s a magnet. But in my North-lands, it’s a magical artifact that intensifies the magical powers of a mage.

Different cultures in different time periods and different locations of my North-lands possess different names for mages.

In the Steam Age, the people of Silmaren call them keyholders, the denizens of Fiorish use the term seer, while the citizens of Auberon say patternmaster or enigmologist. There are more variations, but I’m not going to list them all here. 😉

The five lodestones rattling around the “modern”-day North-lands came out of ancient Navarys. So for the duration of this post, I’ll use the term favored by the ancient Navareans: fabrimancer.

The Navareans called their magic energea and their magical focus stones were energea-stones, not lodestones. The lodestones were created at the end of Navarean history, not its beginning, and I’ll get there soon. Promise. But first I must talk about energea-stones.

The Navareans called their magic energea and their magical focus stones were energea-stones, not lodestones. The lodestones were created at the end of Navarean history, not its beginning, and I’ll get there soon. Promise. But first I must talk about energea-stones.

Energea-stones were crafted from the remains of a meteor fragment lodged in the mountainside of the isle of Navarys. To the ordinary eye, they look like small black pebbles—about the size your thumb-tip—with a shiny finish. (A few were made at larger sizes, but the vast majority were small.)

Energea-stones have been around for almost as long as the Navareans themselves (from pre-history and the age of reed huts). The Navareans learned about fabrimancy (magery) from the energea-stones, rather than fashioning the stones after they developed fabrimancy.

Energea-stones have been around for almost as long as the Navareans themselves (from pre-history and the age of reed huts). The Navareans learned about fabrimancy (magery) from the energea-stones, rather than fashioning the stones after they developed fabrimancy.

To a fabrimancer’s eye (if he or she is a visual practitioner, not an aural one or a kinesthetic one), the stones hold spiraling patterns of silvery light. This light is the visual manifestation of energea, of magic.

But more important than what energea-stones look like is what they do and how they do it.

In Navarys, an energea-stone would be shaped by a specialist to do a specific task, such as spinning a spinning wheel or a grain mill, tossing a shuttle across a weaver’s loom, or winding the rope of well bucket around a spool. Or the stone might be formed to simply magnify a fabrimancer’s power.

Different stones performed different tasks, but the Navareans especially liked to use them for semi-automating the tasks of craftsmanship. And they wished the stones could be fashioned to permit full automation. It was a sort of holy grail with them.

Energea-stones required the presence of a fabrimancer channeling his or her energea through the stone, almost as though the fabrimancer were a sort of living battery funneling electricity through an engine.

The lodestones were the breakthrough Navareans had been hoping for.

A lodestone looks a lot like an ordinary energea-stone—a small black pebble—except its surface finish is a velvet matte, not shiny. Like energea-stones they can be fashioned in different sizes for different purposes.

A lodestone looks a lot like an ordinary energea-stone—a small black pebble—except its surface finish is a velvet matte, not shiny. Like energea-stones they can be fashioned in different sizes for different purposes.

But a lodestone draws energea from its surroundings at large, not just from the fabrimancer wielding it. And thus a lodestone permits true automation. It must be forged so as to direct the energea flowing through it to perform the task desired. But once the fabrimancer sets it going, the lodestone does its work until the fabrimancer halts it. The fabrimancer can actually walk away from the work in progress.

Unfortunately, the lodestones embody one serious danger not possessed by ordinary energea-stones.

When an energea-stone is used by a fabrimancer to magnify and concentrate his magical powers, the stone also acts as a sort of overflow valve. If the fabrimancer loses control and summons too much energea—a potentially destructive amount—the excess is channeled away through the stone without doing damage to the fabrimancer.

Lodestones don’t possess this safety feature. Instead, they always carry exactly half of the energea summoned by the fabrimancer. Which means that if the fabrimancer summons a damaging amount, it does damage. Specifically, it tears the energetic structures that underlie the fabrimancer’s physical being.

That damage manifests as the troll-disease that appears in so many of my North-lands stories.

Only six lodestones were originally created. One of them—the largest—sank to the bottom of the great ocean. The other five are loose in the world, creating trouble when they are found.

Skies of Navarys tells the story of the creation of the lodestones, through the eyes of a pair of teenagers.

Skies of Navarys tells the story of the creation of the lodestones, through the eyes of a pair of teenagers.

The Tally Master follows one of the lodestones into the hands of a troll warlord, where an honorable accountant and his assistant determine the outcome of the encounter.

Resonant Bronze shows how a lodestone might turn the tables on the troll horde.

Rainbow’s Lodestone and Star-drake recount the fate of a lodestone used to commit an evil deed.

And To Thread the Labyrinth, due out in March 2019, sees a lodestone returned to a place of proper oversight, although the larger story focuses on a troll-witch hiding her troll-disease.

For more about ancient Navarys, see:

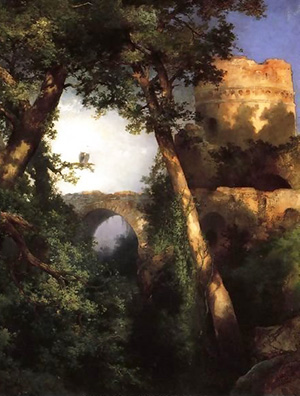

A Tour of Navarys

From Navarys to Imsterfeldt

For more about the magic of the North-lands, see:

Magic in the North-lands

Magic in Silmaren

Radices and Arcs