My second reader gave me feedback on Fate’s Door this Monday, and I am now in the final round of revision. I’m excited!

Both my first reader and second reader are fantastic. They see any problem areas that escape my perception, and often have great suggestions for how to fix them. All my books are better, because of their contributions.

Each had kind words to say about Fate’s Door, and my second reader waxed lyrical about how good the ending made her feel.

I estimate that my revsions will take me 3 weeks. Proofreading will take another week. And then I’ll be uploading the files to Amazon. Woot woot! 😀

I estimate that my revsions will take me 3 weeks. Proofreading will take another week. And then I’ll be uploading the files to Amazon. Woot woot! 😀

I’m aware, of course, that I originally named September as my release month. (For Fate’s Door and my other four upcoming books.) And then I thought October was likely.

Now October has arrived, and I’m aiming for November.

The difference between the previous estimates and this one is that the remaining tasks are all under my control. When I’m waiting on my kind readers – who are generous volunteers, after all – I must respect the fact that they have their own full lives, into which they wedge the beta reading of my books. Which means there is some degree of uncertainty as to when I’ll receive their feedback.

Since I write full time, I can now pound from dawn to dusk, galloping toward the finish line.

Among myriad other revisions, I’ve cut four chapters from the middle of the book. I love the scenes in them, but they possess too little action and slow the pace of the story in a place where the pace needs to be brisk. So out they go. Fate’s Door will be better without them.

However, I think that some of you who frequent my blog might enjoy them as vignettes from Nerine’s world, so I’m going to follow in other writers’ footsteps and share some of the cut chapters here.

I’ll need to review the cut material for spoilers, but the old chapter 18 doesn’t have any.

Eilidh is Nerine’s bossy elder sister.

18 ~ Eilidh and the Olympians

After nearly two déka-days of travel beneath the sea, they arrived at Thérma and went ashore, a little to the south of the port of the land people.

The water of the lagoon where they tethered the chariot was very still, and the strip of sand, between the water and the glade of arbutus and olive trees, very narrow.

The moment Nerine and her escort breached the air, the sweet sounds of pipes, backed by the beat of drums and the murmur of strings, met them.

Nymphs danced across dappled grass to greet them and draw them toward a festal table, laden with tureens of berries, platters of cakes, and carafes of wine.

“Welcome! Welcome!” called their hosts.

Nerine was not permitted to feed herself. The merry crowd popped morsels into her mouth as first one and then another twirled by her. Then she was drawn into the dance and passed from one laughing maiden to another. She never managed to distinguish one individual from another – they were all white-frocked and curly-tressed and constantly in motion. When Nerine eventually came to rest, they garbed her in one of the gowns of her trousseau – of aqua silk, with many draping folds – and led her away to a clearing where a winged horse awaited her, chafing and stamping.

She was allowed a mere moment to bid the sea warriors farewell before the nymphs boosted her onto the pegasus’ back, one of them climbing up behind her.

“Grab his mane,” instructed the nymph.

Nerine grabbed. The horse hairs felt almost silken against her palms and fingers, but they were very strong, and not slippery.

The downsweep of their steed’s wings sounded thunderous in her ears, drowning the ever-playing music. Her spine compressed as the creature leaped into the air. Then they were aloft, and it was magical, more amazing than the time she’d climbed the stairs to the top of the beacon tower on Altairos’ island.

The pegasus flew far higher, circling up and up, so that she could see the canopy of the green woodland stretching away below, and the land dwellers’ city at its edge to the north, strange and different, with fluted columns and triangular pediments and double-slanting roofs.

The air was all about her, like water, but more invigorating, the sun dazzling her eyes. She felt breathless and wondered if she should worry about falling, but her steed’s back was very broad and secure, and the nymph behind her had wrapped steadying arms around Nerine’s waist.

She gave herself over to the wonder of traveling the sky. Was this why Lord Zeus had chosen to rule the airs above the ground, when he and his brothers divided the world between them?

In the distance, a vast mountain rose, its slopes green and steep, its rocky peak gleaming with snow. Mount Olympus, the seat of the gods themselves. Nerine could hardly believe that she would be a guest there. It had always seemed a far-off reality that bided on the fringes of her experience, never destined to come closer, certainly never to approach her very center. But here she was.

The pegasus soared at a tremendous speed, although the winds seemed to part for it, never tousling Nerine’s hair. And the mountain slope drew rapidly nearer, the peak towering far overhead, its skirts plunging far below.

They landed in a cup of flower-strewn meadow just below the rocky cliffs of the peak, greeted by yet more white-clad maidens, although these were more stately than the nymphs in the celebration by the shore.

When Nerine caught sight of her eldest sister – Eilidh – she realized that these were Queen Hera’s handmaidens, and that she had been granted great honor.

Eilidh came forward first, her white gown glinting with threads of silver, and a tiara of pearls in the complicated braids and swirls of her pinned-up blond hair. She looked even more grand than when she’d departed home, with more dignity in her carriage, a loftier tilt to her chin.

Nerine prepared herself to withstand her sister’s airs and graces. This wasn’t home. She couldn’t be rude when Eilidh was condescending.

But Eilidh was not condescending.

Her face held genuine pleasure, and her embrace felt sincere.

“Queen Hera bids you welcome and invites you to enjoy the hospitality of her abode, whilst the preparations for your journey to Scandia move toward their completion,” said Eilidh. The words were formal – likely had to be, under the circumstances – but her tone was warm.

Apparently Eilidh had been changed, and for the better, by her sojourn under Hera’s rule.

She introduced Nerine to her companion handmaidens – Akráia, Argéia, and so on – but there were too many and Nerine lost the names almost as soon as Eilidh spoke them.

“You must be tired, dear sister,” said Eilidh. “It is a long journey from Pelagie to Olympus. Let us attend to you and soothe your cares and aches.” She linked her arm through Nerine’s and guided her into the trees at the edge of the meadow and along a winding path, the handmaidens following behind them.

Nerine was not tired, still exhilarated by her ride through the sky, but she was willing to fall in with whatever plans had been made for her.

A cool breeze rustled the leaves above, and the clear clean scents of northern flowers rose from mossy ground between the tree trunks, so different from the warmer dusty, musky aromas of Pelagie.

After a short walk, they arrived at a circular shrine set in amongst the trees. Two shallow steps led up to a low dais where fluted columns upheld the domed roof. Within, carved screens surrounded a center fountain.

The handmaidens pinned Nerine’s hair to her head, removed her gown, and led her into the fountain to bathe.

The water felt strange on her skin, cool and almost too pure, with an edge to its purity.

It must be fresh water, not salt, she realized.

When she emerged from the bath, the handmaidens smoothed unguents perfumed with wild cucumber – a mild, bracing scent – into her skin and brought yet another gown, this one of pale green silk, to clothe her.

They guided her to a square shrine at the end of another forest path. No screens sequestered its heart within the surrounding columns, and Nerine could see divans and low tables scattered upon rich carpets. Eilidh awaited her there, insisting that she recline while another handmaiden brushed Nerine’s hair, and a third offered her rose-infused water to drink.

Nerine accepted a few sips of the infusion, enjoying its lovely and light flavor, but then insisted that she needed nothing more to eat or drink. There had been plenty at the party on the shore. The handmaiden with the brush and comb was very gentle, and the sensation of the implements against the few tangles in Nerine’s curly tresses, pleasant.

Eilidh, perched gracefully on a low stool beside Nerine’s divan, chattered about life in Hera’s cortege. It seemed to consist of welcoming a constant stream of visitors, serving as a subsidiary host at the many feasts, amusing Hera herself with song or poetry or dancing, and occasionally running errands for her.

It sounded repetitious to Nerine, and lacking in solitude, but Eilidh seemed to like it.

Eilidh did ask Nerine to tell her all about events at home and about Nerine’s decision to accept a position with the norns, but Eilidh’s habits were against her. Despite her sister’s real interest in Nerine’s answers, she didn’t have much practice in listening.

The handmaiden with the rosewater took over the conversation, asking Nerine questions and listening attentively.

There wasn’t really much to say about events at home, and Nerine had no intention of sharing her private tragedy, but the handmaiden was intrigued by Nerine’s accounts of nålbindning knitting. She persuaded her to demonstrate the skill, using a beautiful peach-hued silk yarn.

At the evening feast, Nerine saw more clearly how well her sister fit into her setting.

* * *

The banquet was held in a large temple on a rocky ridge above the trees. The building was structured in the way that Nerine was learning was typical amongst the Olympians: a low plinth reached by three shallow steps, with fluted columns set in far enough to create a surrounding walkway. The rectangular shape seemed far more common than the round one of the shrine where she had bathed, or the square one where she had rested.

The banquet hall was not only rectangular, but huge! Perhaps as large as the entire central court of King Zeron’s palace. Stone walls sheltered the space within the columns, but its many doors stood open, providing magnificent views over the nearby ridges as the sun set.

Nine of the greatest Olympians occupied their magnificent divans, but Nerine – attending under Hera’s aegis – was presented only to Queen Hera.

Queen Hera’s divan, elevated on a low dais, was fashioned of scented applewood and adorned with peacock feathers, the metallic blues and greens of their eyes glinting in the light of the many oil lamps. The queen herself did not recline, but sat erect when Eilidh drew Nerine forward.

Hera’s gown of garnet silk embroidered with gold lilies complemented her statuesque beauty, but it was her immense presence – like the majesty that hung around King Zeron, but far, far greater – that made Nerine’s knees tremble as she executed a land person’s bow.

Hera merely nodded her acknowledgement and addressed the cupbearer offering her cherries. Her voice was low and sweet.

Eilidh guided Nerine to a divan in those clustered around the dais, seated her, and returned to the queen’s side.

Cupbearers served Nerine – the delicacies prepared for the tables of the gods were exceptional, perfectly toasted meringues, stained “glass” panes made of crystallized honey, and so on – but Nerine’s focus remained on her sister.

Eilidh conversed with Queen Hera. She delivered a particularly succulent apricot half from Hera to Lord Zeus. She played the lyre at the queen’s request. She circulated amongst Hera’s guests, even returning to Nerine for an interval to converse about the special bond between the pegasi and the muses.

Eilidh performed all her duties flawlessly, but that was not what riveted Nerine’ s attention. It was Eilidh’s demeanor. At home in the reef palace, Eilidh’s haughtiness had annoyed Nerine nearly every day. It had seemed conceited and pretentious.

On Mount Olympus – with nine of the greater gods looking on, each of whom bore the astounding majesty that mantled Hera, a few sustaining even weightier potency – Eilidh’s pride looked very different.

It wasn’t pride, Nerine realized.

It had transmuted into self-respect.

And not all of Hera’s handmaidens possessed enough. One blushed furiously whenever Hera’s attention fell on her. Another giggled too often. Yet another angled for the divine attention, hoping to curry favor.

Eilidh’s demeanor was perfect, conveying reverence for the great beings she served, while yet reserving recognition for her own worth.

And that was why Eilidh could now greet her once-disdained sister with genuine warmth. Eilidh lived in circumstances which both fed and demanded dignity, and thus no longer needed to exercise her talents inappropriately.

Eilidh truly had found home.

* * *

For the next extra chapters from Fate’s Door, see:

Nerine’s Youngest Sister (Agnippe and Mount Helicon)

The Nine Muses of Antiquity (Agnippe and the Muses)

Hera’s Handmaidens (Eilidh’s Farewell)

To purchase and read Fate’s Door: Amazon I B&N I iTunes I Kobo I Smashwords

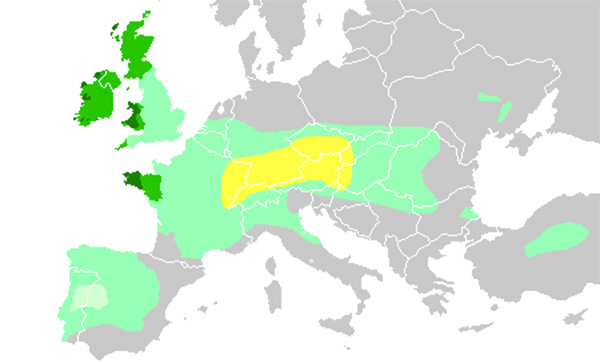

Additionally, there were established trade routes north from the Aegean following the Vardar River and then the Great Morava River to the Danube.

Additionally, there were established trade routes north from the Aegean following the Vardar River and then the Great Morava River to the Danube.