I cut four chapters from the middle of Fate’s Door.

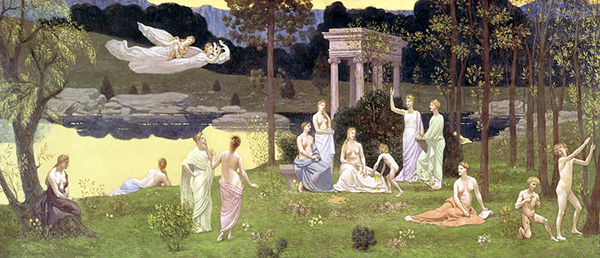

It was a lot of fun hanging around on Mount Olympus with Nerine and her eldest sister Eilidh. It was even more fun joining Nerine and her youngest sister Agnippe on Mount Helicon.

But I was indulging myself. All that loitering with the Greek gods brought my story to a near stop. So I reduced those chapters to a series of brief vignettes.

But I suspect some of my readers might enjoy dallying within Greek mythology as much as I do.

For those of you who share that taste of mine, here is a part of chapter 19 that was cut from the final manuscript. 😀

Amidst the chattering opulence of Hera’s handmaidens Nerine possessed neither intimacy nor solitude. And she’d never hankered for luxury.

Groups and clusters seemed the natural mode of the handmaidens. They never walked alone or even in pairs.

All except one.

That one loner was a brunette who wore her hair in a simple braid circling her head, and who chose gowns of pale gray or pastel blue rather than the popular variations on white. When the handmaidens gathered to brush one another’s hair, the brunette sought the fountain shrine to bathe alone. If the handmaidens danced in the meadow, she walked the forest paths. Alone.

Nerine was reluctant to interrupt her solitude. Nor was she certain she wanted to draw attention to her by asking someone. But she was curious about this young woman who didn’t seem to fit in. Why was she on Mount Olympus? What was her role?

Before Nerine could learn much, Eilidh suggested a visit to Agnippe.

“You’re so close,” she said. “What a shame to miss the chance!”

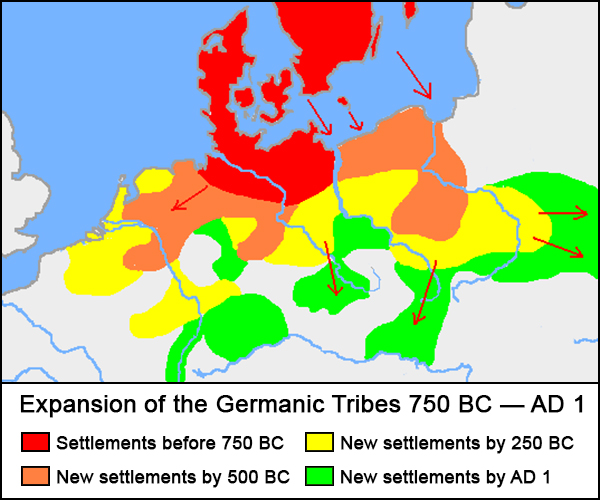

Nerine hadn’t realized Mount Helicon rose nearby. Was her knowledge of Hellene geography so poor? No, she’d forgotten that the winged horses brought locations closer. The ten-day trek to the glades of the muses would be a mere morning’s flight aback a pegasus.

The valleys around Mount Helicon were less wild than the ridges around Mount Olympus – featuring olive groves – and the snow was gone from its peak.

Nerine alit amidst grasses on the mountain skirts, where a group of youths wearing sheepskins slung over one shoulder awaited her. Were they shepherds from the local village?

“Welcome, numen!” said their spokesman. “We shall guide you to the sacred spring.”

This was the first evidence she’d seen of direct contact – rather than spiritual connection – between mortal and divine. The young men clearly knew their way, leading her through bushy laurel trees and tall elms. They spoke in a dialect unfamiliar to her, and cleared fallen twigs from the path as they walked.

The sacred spring issued from a cleft in a low cliff to fill a pool, rushes growing in its shallows, and ringed by crab apple trees and wild roses. The water was very clear, with dancing dapples cast by its motion across the spring bottom.

As Nerine approached, Agnippe rose from the depths to stand amidst the rushes – slender and girlish; not yet entered into full womanhood – water streaming from her pale skin. She wore a belt and pectoral fashioned from small plates of nacre, and the sun lit rainbows in their gleaming surfaces. Her tightly curled blonde hair had grown to hang past her hips. She was luminously beautiful.

The shepherd boys faded away, leaving Nerine alone with her sister.

Agnippe didn’t hesitate – despite her dampness. She leapt to the spring bank to wrap Nerine in glad arms.

“Nerine! Nerine! Oh, Nerine!”

Nerine burst into tears. Seeing Agnippe after so long, feeling Agnippe’s embrace – it overwhelmed her.

“I’ve missed you,” gasped Nerine. “I’ve missed you so much.”

Agnippe laughed tearily. “I’ve got your gown wet. I’m sorry.”

“Can I see your spring? Is it permitted, or–?” Or was only the spring’s guardian allowed to enter the water. Nerine had a sudden longing to be underwater with her sister as though they were both at home in the reef together.

Agnippe waved one hand in a gesture of welcome and smiled, dashing the tears from her cheeks. “Only my permission is needed, and you have it. Come in!”

Nerine slipped out of her gown and entered the water bare, as though she were a little girl, needing no garb save her own skin. The spring was very cold, with that strange edge to it that fresh water possessed, although this felt mellower than the fountain on Mount Olympus.

Minnows darted amongst the rushes in the shallows. A frog hopped, splashing.

The water deepened, and Nerine submerged. Her spiracles opened, and she could taste the spring: sweet and refreshing and with a slight mineral tang that appealed. Agnippe appeared by her side.

“Do you like it? Can you tolerate the freshwater?” She looked anxious.

“It’s lovely. I love it!” Nerine reassured her.

Agnippe wanted to show her everything about her diminutive domain.

The flag lilies growing on the far bank, the gleaming snails, the water-smoothed pebbles, the swimming trout, the crayfish and – best of all – the underwater cave that stretched back under the cliff, with twisting passages and varied chambers. In one, a torrent from the heart of the mountain turned the water frothy with bubbles. In another, a cleft in the rock admitted a shaft of strong sunlight, striking sparkles of gold and silver from the surrounding stone.

Agnippe’s possessions from home occupied the inmost chamber.

Nerine couldn’t help admiring Agnippe’s underwater mansion, but she was relieved when they returned to the outside pool and could see the sky again, its warm blue fractured by the moving surface of the spring above them. The darting fish made the pool feel lively, friendlier, than the cool beauty of the caves.

“Do you stay in the water all the time?” asked Nerine. She’d imagined Agnippe on land, surrounded by the muses, with only brief sojourns in the spring. Why else would Agnippe have required a trousseau as extensive as Eilidh’s?

“Of course not!” Agnippe sounded surprised. She started to explain, then stopped and took Nerine’s hand. “Nerine . . . I don’t want to pry –” she looked younger than she had when Nerine first set eyes on her sister emerging from the water, and her voice sounded uncertain – “but, what are you doing here? I mean –” her voice strengthened – “it’s lovely to see you, but you aren’t just visiting me, are you? You’re traveling far into the north with the intent to stay.”

Agnippe drifted forward to kiss Nerine’s cheek. “I want you to be as happy as I am.”

Uneasiness stirred in Nerine’s belly. How could she explain her decision to her sister? She couldn’t bear to rehash the events that had led up to it. She didn’t want to simply shut Agnippe out by not answering at all. She refused to lie.

Sighing, she attempted to gather her thoughts. “You felt a real calling to be guardian of this spring of inspiration, didn’t you?”

Agnippe nodded.

“And I know Eilidh longed to join Queen Hera’s entourage,” Nerine continued. “She seems . . . more certain, more . . . anchored than I’ve ever known her to be. Have you seen her? Since you settled here?”

“She’s who she was meant to be, I think,” agreed Agnippe.

“Yes, that’s it exactly.” Nerine sighed again. “I think that’s what you were hoping for me. Am I right?”

Agnippe’s face looked very solemn, but she didn’t speak.

“And you fear I am making a mistake.” Nerine squeezed Agnippe’s hand.

“Are you?” Agnippe’s voice was very low.

“I might be, but I don’t think so. I don’t feel the same kind of calling that you and Eilidh feel. Or Tyr.” Their brother definitely loved his Tyrrhenian Sea, loved caring for it, loved living in it. “But waiting at home to figure it out . . . wasn’t working for me. I had to leave!” That burst out of her more strongly than she’d meant it to.

“But why Scandia?” Now Agnippe sounded upset. “I’ll never see you! And what will you do, if you discover your true calling – something other than weaving – once you’re there? You’ll be stuck!”

Nerine wasn’t sure which of those concerns to address first.

“I won’t be stuck,” she insisted. “How would the norns be seeking a handmaiden unless the previous one had left?”

“You’re going to them without making a real commitment?” Agnippe sounded shocked, no doubt because her own commitment to her spring had been so immediate and intense.

“I don’t go lightly,” Nerine contended. “I shall learn all that they need me to, that I may fulfill my duties well. I shall give them the best that is in me. And I have some skill with textiles already.”

Agnippe’s brow wrinkled. “But . . .”

Nerine swirled her right foot in the cool water. “Eilidh is everything a handmaiden is meant to be, but some of the others . . . are not. Some are too intimidated by the divine presence. Some are there on Olympus for what they can gain for themselves. Some . . . may grow into their roles. But I doubt that all of them will stay to attend on Hera forever. Even our sister may one day wish for something different.”

“That’s true,” Agnippe assented. “But it’s a little different, isn’t it? Queen Hera must have more than three dozen handmaidens. The norns . . .”

“. . . will just have me,” finished Nerine.

Agnippe snorted. “You’ll never be a ‘just’ anything,” she said.

Nerine laughed. “Why, thank you!”

They hung in the water, silent for a moment, the golden dapples on the spring’s floor shifting below them.

“I see your point,” Nerine admitted. “I know nålbindning and embroidery. I am proficient with a ground loom.” She glanced at her sister. Was she revealing too much? Would Agnippe follow up with awkward questions?

No, Agnippe was merely listening – intently – interested in where Nerine was going with this, not worrying about details such as how her sister had learned to use a ground loom.

“I am careful and neat. But the norns will be teaching me . . . more than I can well imagine.” She shook her head. Weaving was one thing. Weaving fate? Something wholly beyond her experience. “If I were going to them with the intention to leave, I would be wronging them. But, Agnippe” – her voice cracked, ever so slightly – “I don’t think I will sort myself out for . . . years. If ever.”

Sudden strain shadowed Agnippe’s eyes.

“I believe I’ll be in Scandia for . . . quite some time.” Nerine squeezed Agnippe’s hand – still in hers – again. She hated to see her sister looking so worried for her and injected a jolly tone to her words. “I promise I’ll come visit you! And . . .” more seriously “. . . I do think that weaving fate with the norns is right for me. For now, even if not for ever.”

Agnippe nodded more slowly. “I think I see,” she said. “I just wish . . . you had an easier current to swim.”

Nerine sighed again, then became brisk. “So do I!”

They laughed together.

It was good – so good – to understand and be understood, to connect at depth with a friend – who also happened to be a sister.

For the next extra chapters from Fate’s Door, see:

The Nine Muses of Antiquity (Agnippe and the Muses)

Hera’s Handmaidens (Eilidh’s Farewell)

For the first extra chapter from Fate’s Door, see:

Update on Fate’s Door (Eilidh and Mount Olympus)

To purchase and read Fate’s Door: Amazon I B&N I iTunes I Kobo I Smashwords